Why Time Raises Intrinsic Value in Wide-Moat Stocks

A stable competitive advantage period lets intrinsic value compound, even without changing assumptions

Most DCF models assume your ability to forecast declines over time. That’s why most investors use 5- or 10-year DCFs. And with most businesses, that’s exactly what happens. Competition increases, market conditions change, and confidence in long-term projections starts to fade.

But that doesn’t apply to all businesses.

With the right attributes—durable moats, low risk of disruption, and high barriers to entry—you can keep your forecast period stable over time. Ten years today is still ten years next year.

That might not sound like much, but it matters. A stable forecast period means you’re effectively adding another year of excess cash flows every year. All else equal, that consistently raises intrinsic value.

In this post, we’ll look at the kind of businesses that let you do just that.

Valuation Doesn’t Matter (That Much)

You probably hear it all the time: for the best businesses, valuation doesn’t matter that much. That’s the view of top investors like Chuck Akre, Nick Sleep, Terry Smith, and Warren Buffett.

Terry Smith famously explains how you could have paid a P/E of 281 for L’Oréal, 174 for Brown-Forman, and 100 for PepsiCo and still earned a 7% annual return. The point isn’t that valuation doesn’t matter, but that the best businesses outrun almost any reasonable model of future cash flows.

Why? Because their competitive advantage period (CAP) doesn’t shrink. Had you made a 10-year DCF model for L’Oréal in 1973, you would have missed over half a century of excess cash flows (that is, cash flows where ROIIC is above the cost of capital). And even today, L’Oréal’s CAP hasn’t collapsed: the forecast period remains long.

Warren Buffett’s line about buying a wonderful company at a fair price captures the same idea: in the right business, time does the work.

Of course, valuation does matter—just not equally for every business.

For weak businesses or businesses in a rapidly changing industry, valuation is critical, because the margin for error is thin. But for durable companies—where the forecast period doesn’t decline—valuation matters less.

The best investors recognize that overly short models miss the majority of value in these kinds of businesses. But you never hear investors like Nick Sleep or Chuck Akre obsess over modeling precision. Even if they don’t articulate it in discounted cash flow terms, they act as if the business will keep compounding beyond the standard horizon. And if that’s true, it means intrinsic value is rising over time.

So when investors say “valuation doesn’t matter”, what they really mean is: the long-term returns are predictable enough, and valuable enough, to consider price less important. And that only happens in a small class of businesses.

Businesses With Stable Forecast Periods

So what kind of company lets you keep the forecast period stable?

They’re rare, but they exist. The key is predictability. If the economics don’t change much, the moat remains stable, and the industry isn’t moving rapidly, there’s no reason to assume a short forecast window.

More specifically, these businesses tend to share a few attributes:

High return on incremental invested capital (ROIIC)

The forecast period should only include years where ROIIC exceeds the cost of capital. Once returns fade, you shift to the terminal value. So if you want to hold the forecast period steady, you need a business that can reinvest at high rates consistently.

Low risk of disruption

Disruption collapses the forecast period. You can’t assume 20 years of excess returns when the business might not exist in ten. Industries where the risk of disruption is low are thus more favorable.

Slow-changing industries

Rapidly changing industries are unpredictable. High barriers to entry, stable market shares, no pricing wars, and secular tailwinds are all beneficial in an industry. Stability helps keep the forecast period intact.

Wide, durable moats

The moat is what allows the business to reinvest at high rates consistently. For the forecast period to remain stable, there must be a wide moat.

Companies like Moody’s and Costco check all these boxes. Besides generating strong returns today, you can confidently predict those returns will still be there 10-20 years from now. It’s why despite seeming perpetually overvalued, such stocks always continue to perform.

How It Shows Up in the Math

Mathematically, the concept is simple.

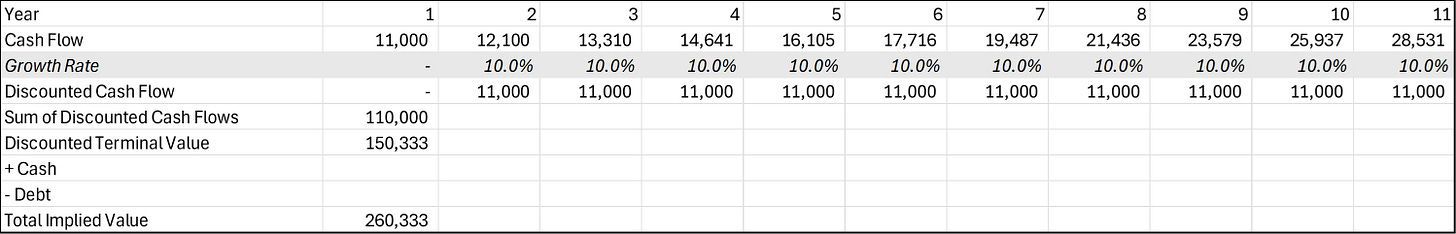

Take a business growing cash flows at 10% per year for 10 years, then transitioning to a terminal value. Starting cash flow is $10,000. With a standard DCF, including a typical 10% discount rate and 2.5% terminal growth rate, that gets you to a valuation of around $237,000.

Now assume we’re one year forward. If this is a business that checks all the boxes—high ROIIC, stable industry, low disruption—you don’t need to shorten the forecast period to nine years. You can keep a full 10-year forecast.

As a result, the valuation increases to ~$260,000.

Two things have changed:

The future cash flows are one year closer, so they’re discounted less.

One more year of excess cash flow has been added to the tail: year 11 is now part of the explicit forecast instead of the terminal period.

This is the key point. Intrinsic value increased without any change in assumptions. No higher growth, no margin expansion, no lower discount rate.

Just time passing.

This is what makes these business valuable. Not just because they grow, but because the competitive advantage period stays wide year after year.

A Real-World Example

Let’s bring the idea to life.

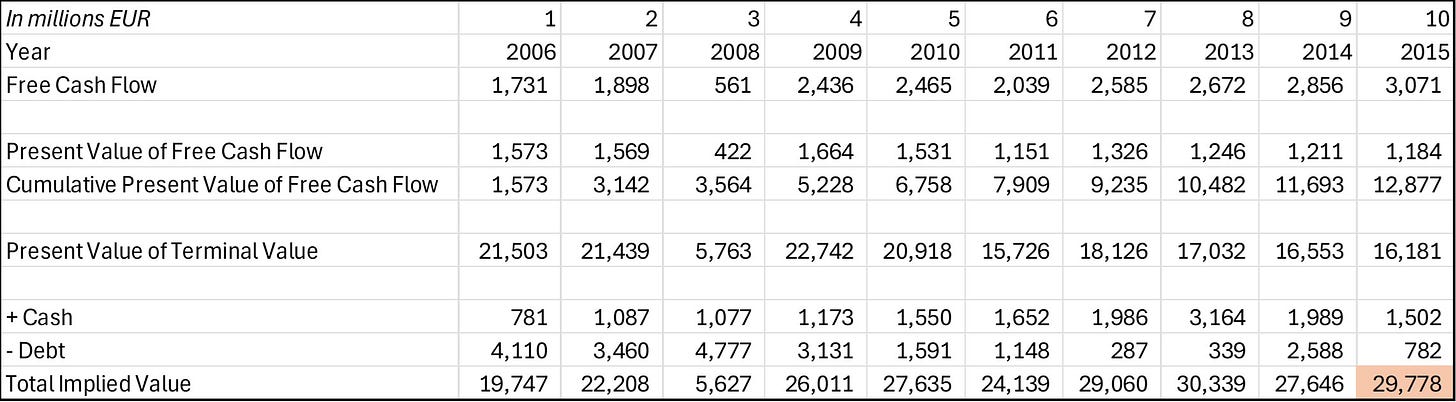

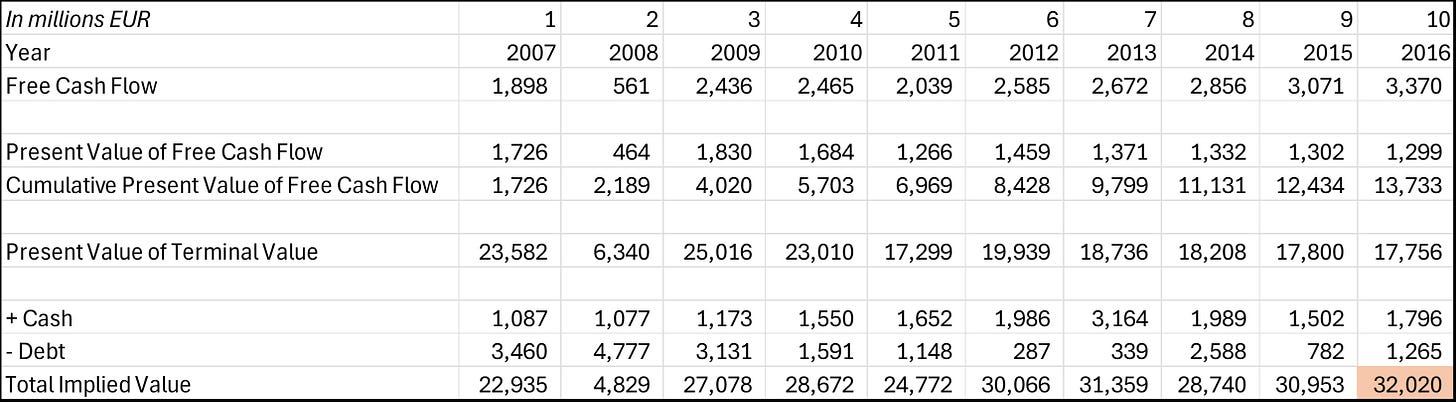

Suppose at the end of 2004 you built a 10-year DCF for L’Oréal using actual free cash flows. That model—with a 10% discount rate and 2.5% terminal growth rate—produces an intrinsic value of €26.4 billion. At the time, its market cap was around €50 billion.

You repeat the same process the next year: same model, updated starting free cash flow. You do it again in 2006. Again in 2007.

Each time, the forecast period rolls forward. But the model stays ten years long, because L’Oréal continues to reinvest at high returns, faces no disruption, and operates in a predictable industry. In short: the competitive advantage period doesn’t decay.

As a result, intrinsic value consistently rises, with a brief dip between 2010 and 2013. The dip reflects weaker cash flows in 2020-2023 due to the pandemic—years that fall inside the 10-year forecast window of those models.

The broader point still holds: L’Oréal’s intrinsic value compounds over time as the forecast period remains stable. And despite always appearing overvalued, the stock continued to rise. That suggests a 10-year model systematically understates value for businesses with durable moats.

“Time is the friend of the wonderful business, the enemy of the mediocre”—Warren Buffett, 1989 Berkshire Hathaway Shareholder Letter

In the next post—available exclusively to premium members—I’ll look at three such businesses: companies where time does the work, and intrinsic value rises year after year.

Premium members also get:

One high-conviction stock thesis each month

Monthly Portfolio Letters

Stock updates & in-depth valuations

Exclusive access to our research platform Summit’s Analytics (now in Beta)

Subscribe now and get 30% off: just €105/year (that’s €8.75/month)

In case you missed it:

Disclaimer: the information provided is for informational purposes only and should not be considered as financial advice. I am not a financial advisor, and nothing on this platform should be construed as personalized financial advice. All investment decisions should be made based on your own research.

really liked this one, read it thoroughly, thanks.

It's almost a given that you'll "never" acquire a high-quality company at a low valuation unless a catalyst drives the price down.

Price does matter, even if it doesn't seem like it. For example, you can justify paying a 15-20% premium if it's justifiable in the long run.