We all want to invest in the best businesses—so-called high-quality stocks. A key metric in that search is ROIC, but like any metric, it has its limitations.

A high ROIC can fool investors into thinking they’ve found a great long-term compounder. But strong returns alone aren’t enough.

Many companies with high ROIC are in a mature phase with limited reinvestment opportunities. Just as some stocks are called “Value Traps,” you might consider these “Quality Traps.”

Fortunately, there are ways to separate these stagnant businesses from true compounders. That’s what we’ll cover today.

What You’ll Read Today

Quality Traps

What to Look for Instead

Quality Traps

Quality traps are stocks that seem great on the surface but have an underlying problem that can limit long-term returns. Before defining a quality trap, it’s important to understand what a true compounder is.

A true compounder is a business that consistently reinvests the majority or all of its cash flows at high returns, allowing its value to grow exponentially. These companies prioritize reinvestment because it offers the best potential for long-term growth.

The key factor here is reinvestment. If a company isn’t reinvesting most of its cash flow, it can’t be a compounder—at least not anymore. It may have been one in the past, but as businesses grow, they reach a point where reinvesting everything simply isn’t possible. A company can generate high returns, but without the ability to reinvest them, exponential growth can’t follow.

By definition, companies that distribute a large portion of their cash flow through dividends or share buybacks either lack reinvestment opportunities or generate more cash that they can effectively deploy.

Think of Walmart, PepsiCo, McDonald’s, and even companies regarded as highly as Costco.

Indeed, Costco returns substantial cash to shareholders because:

It generates more cash than it can deploy, or

It lacks significant reinvestment opportunities.

This doesn’t mean these businesses are bad—many are fantastic—but it does mean they’re no longer true compounders.

Nor am I saying the companies mentioned above are necessarily quality traps; I haven’t researched them in depth to make that judgment.

But quality traps do exist. Many of these companies have high ROICs, but ROIC is a backward-looking metric: it reflects returns on capital already deployed. Compounding, on the other hand, is about deploying new capital at high incremental returns.

To be clear, there’s nothing wrong with companies that generate strong cash flows and return capital through dividends and buybacks. That can be an attractive strategy for certain investors. However, for those with a long-term horizon seeking true compounding, these businesses may not be the best fit.

I’ve noticed a common pattern in maturing companies with limited reinvestment opportunities. If invested capital remains flat or even declines, it suggests a company isn’t reinvesting much. However, improved working capital management can also slow the growth of invested capital, which is important to consider and doesn’t necessarily indicate a quality trap.

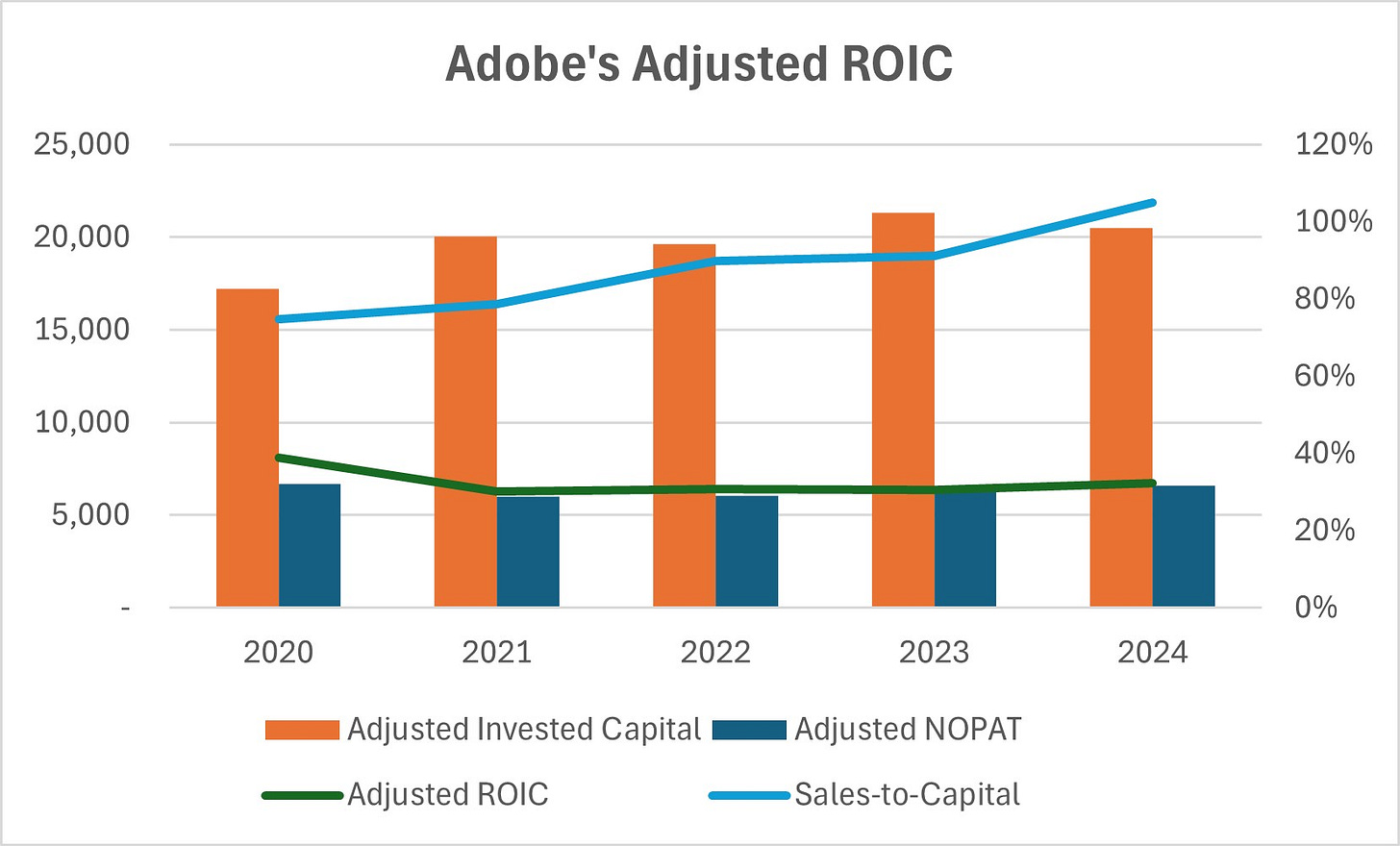

A business can only grow its return so much if invested capital doesn’t expand. Take Adobe, for example. Its invested capital has been flat for the past four years, and NOPAT has also stagnated. Meanwhile, sales do continue to grow, as reflected in the sales-to-capital ratio—but how much further can that go?

And again, I’m not saying Adobe is a bad business. Part of its stagnant invested capital is due to improved working capital management. Still, patterns like these are worth watching.

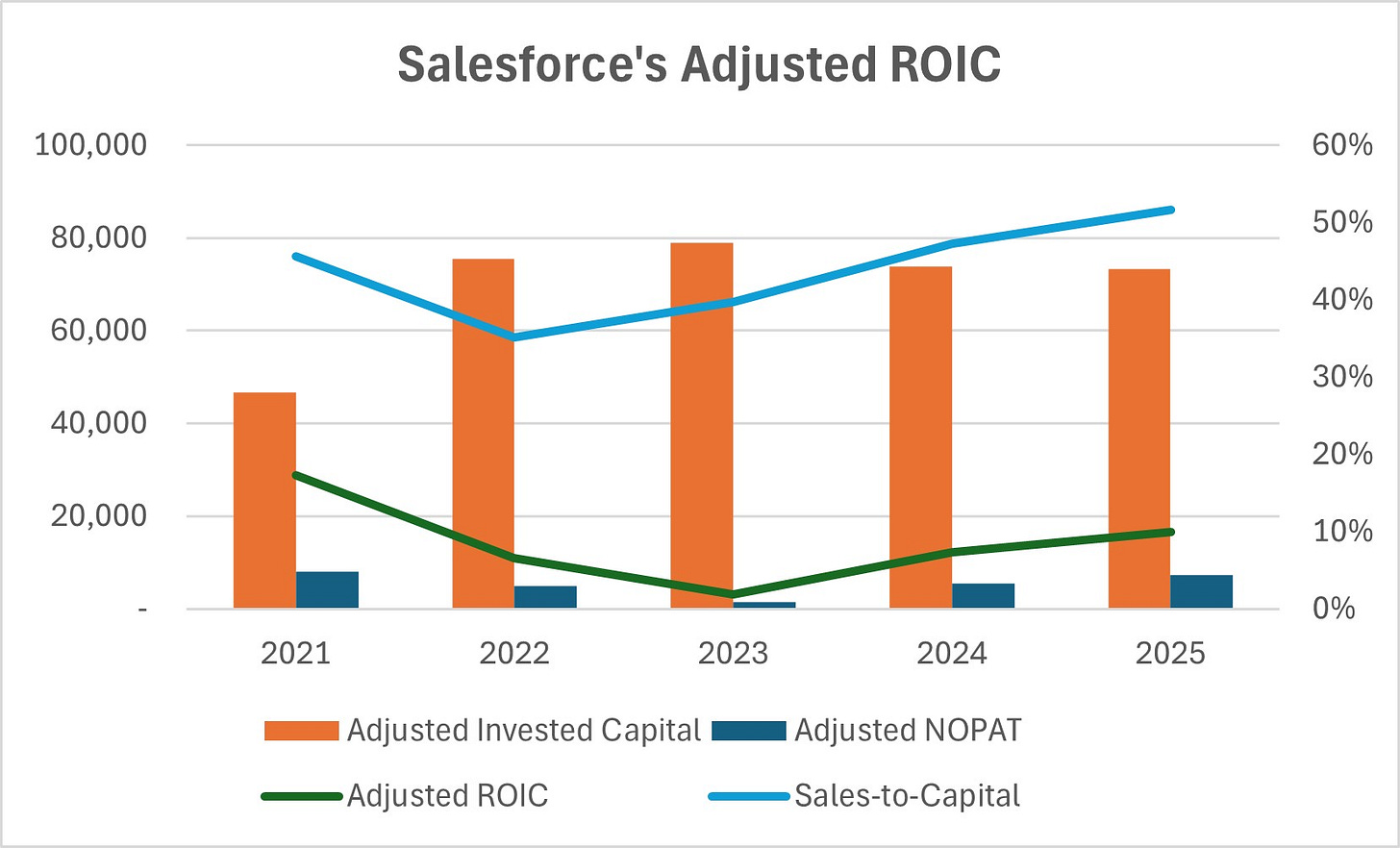

Salesforce, one of my holdings, shows a similar trend. Invested capital is flat, though in part due to working capital improvements. But there’s no denying that Salesforce is maturing—it’s a $270 billion company, after all.

The company’s shift in narrative—from prioritizing growth to focusing on profitability—reinforces this idea. On top of that, Salesforce has initiated a dividend and is aggressively buying back shares. That tells me the company is running out of opportunities to deploy cash at high returns, which makes sense. Salesforce has already built the complete CRM package, and there are few meaningful horizontal expansion opportunities left.

Some businesses can achieve growth without reinvestment, using pricing power or through self-reinforcing network effects. However, such network effects are rare, and strong pricing power may be even rarer.

Reflecting on this makes me think critically of my holdings, questioning whether all of them really align with what I’m looking for. If time is an investor’s best friend, why allocate capital to mature companies when there are businesses out there that can still reinvest all their cash flows at high returns?

So, what should we be looking for? How do we identify true compounders—or those with the potential to become one?

What to Look for Instead

As mentioned earlier, ROIC is a backward-looking metric. ROIIC, on the other hand, offers a forward-looking perspective on returns. Shifts in returns on capital are reflected earliest in ROIIC, providing insights into where ROIC is headed. Naturally, you want to see ROIIC above the cost of capital and, ideally, above ROIC itself.

For ROIIC to remain consistently high, it’s important that invested capital grows, adjusted for intangible investments where necessary. You can’t achieve returns on incremental capital if there is no incremental capital.

Another simple indicator that separates compounders from mature businesses is company size. Large companies often struggle to reinvest their larger cash flows. It’s a similar idea to one of Warren Buffett’s quotes:

“It's a huge structural advantage not to have a lot of money. I think I could make you 50% a year on $1 million. No, I know I could. I guarantee that.”

Being a smaller company with a long runway of growth makes reinvestment easier. For example, Basic-Fit has the entire European market to grow into, presenting clear and abundant reinvestment opportunities.

On the other hand, companies like Walmart, with stores already spread across the US, face increasing difficulty in expanding. Adding new stores becomes harder because their footprint is already so large.

Lastly, capital allocation is key. As seen with Salesforce, a focus on dividends and share buybacks signals that management sees few reinvestment opportunities. Ideally, you want to invest in companies where management reinvests all available operating cash flow, leaving little or no free cash flow. Of course, eventually you expect to reap the rewards, but a long-term investment horizon will benefit from seeing every dollar put back into the business. After all, you invest in a business with the expectation that its management will put your money to work.

The key to distinguishing between compounders and quality traps lies in understanding their reinvestment potential. While both types of businesses can be good or bad investments, compounders—with their ability to consistently reinvest and grow—hold the greatest potential for market-beating returns.

In case you missed it:

Disclaimer: the information provided is for informational purposes only and should not be considered as financial advice. I am not a financial advisor, and nothing on this platform should be construed as personalized financial advice. All investment decisions should be made based on your own research.

Very important distinction when looking at ROIC!

Past success doesn’t guarantee future glory.

For companies to keep soaring, they need plenty of runway ahead—and remember, no business can outgrow its own Total Addressable Market (TAM). Always measure the opportunity before betting on the encore.