Building Smarter DCFs with ROIC and CAP

Why DCFs work better than multiples and how you should tie ROIC and the competitive advantage period into your DCF model

In today’s market—with Trump and tariffs creating havoc—clarity is crucial. Knowing what your stocks are worth, or the price you’re willing to pay, can make all the difference.

There are several ways to value a business. But at the core, intrinsic value always comes down to the same thing: the present value of all future free cash flows. There is no other definition.

That said, not every valuation needs to be a fleshed-out DCF. Multiple-based valuation, for example, can be quick and useful, especially for stocks on the watchlist. For deeper dives, a DCF gives greater insight into intrinsic value.

In this post, we’ll discuss two different valuation methods, explore when each is most useful, and revisit the DCF—specifically how ROIC plays a crucial role in the analysis.

What You’ll Read Today

Multiple-Based Valuation

Using ROIC in a DCF

Buy-In Targets

Multiple-Based Valuation

Multiples are the most common way to value stocks. We can debate their implications another time, but it’s worth noting that a price-to-earnings ratio doesn’t account for risk, capital needs, or the time value of money. It’s an implicit and imperfect tool, yet it can still offer a useful first impression of a stock’s valuation.

One common approach is to project earnings (or cash flow) per share, apply a reasonable multiple, and calculate the implied rate of return based on the forward price. Think of it as a back-of-the-napkin check.

Take ASML, which expects revenue to grow from €28 billion today to somewhere between €44 and €60 billion by 2030. They also anticipate gross margin expansion, so it’s fair to assume some operating leverage and higher net margins as well.

Is we assume a 30% net margin on €44 billion revenue: EPS of around €33

At a 32.5% margin on €52 billion (the midpoint): EPS of roughly €43

At a 35% margin on €60 billion: EPS of about €53

Now, apply a conservative P/E multiple of 25 (well below ASML’s 5-year average of 39), and you get:

A 2030 share price between €838 and €1,334

From today’s price, that implies an annual return of roughly 8.4% to 19%

This is a solid approach if used with awareness of its limitations. Ultimately, however, a DCF is the superior valuation tool.

Using ROIC in a DCF

A discounted cash flow model estimates intrinsic value by projecting future free cash flows and discounting them to the present. Right away, the difference from a multiple-based approach becomes clear. The DCF explicitly accounts for the time value of money, as well as the risk and uncertainty tied to future cash flows, by discounting cash flows. It also considers capital requirements, since free cash flow is calculated after necessary reinvestment—unlike net income, which doesn’t reflect the capital a business needs to grow (unless all investment flows through R&D and SG&A).

Still, DCF models are tricky. In an earlier post, I wrote about the most common DCF mistakes investors make. It was well received, and I wish to revisit one specific part: the forecast period and how it should tie to ROIC.

Most investors use 5- or 10-year models, simply because we have five fingers per hand. But if you’re investing in a durable business expected to generate excess returns for decades, why limit your forecast to just five years?

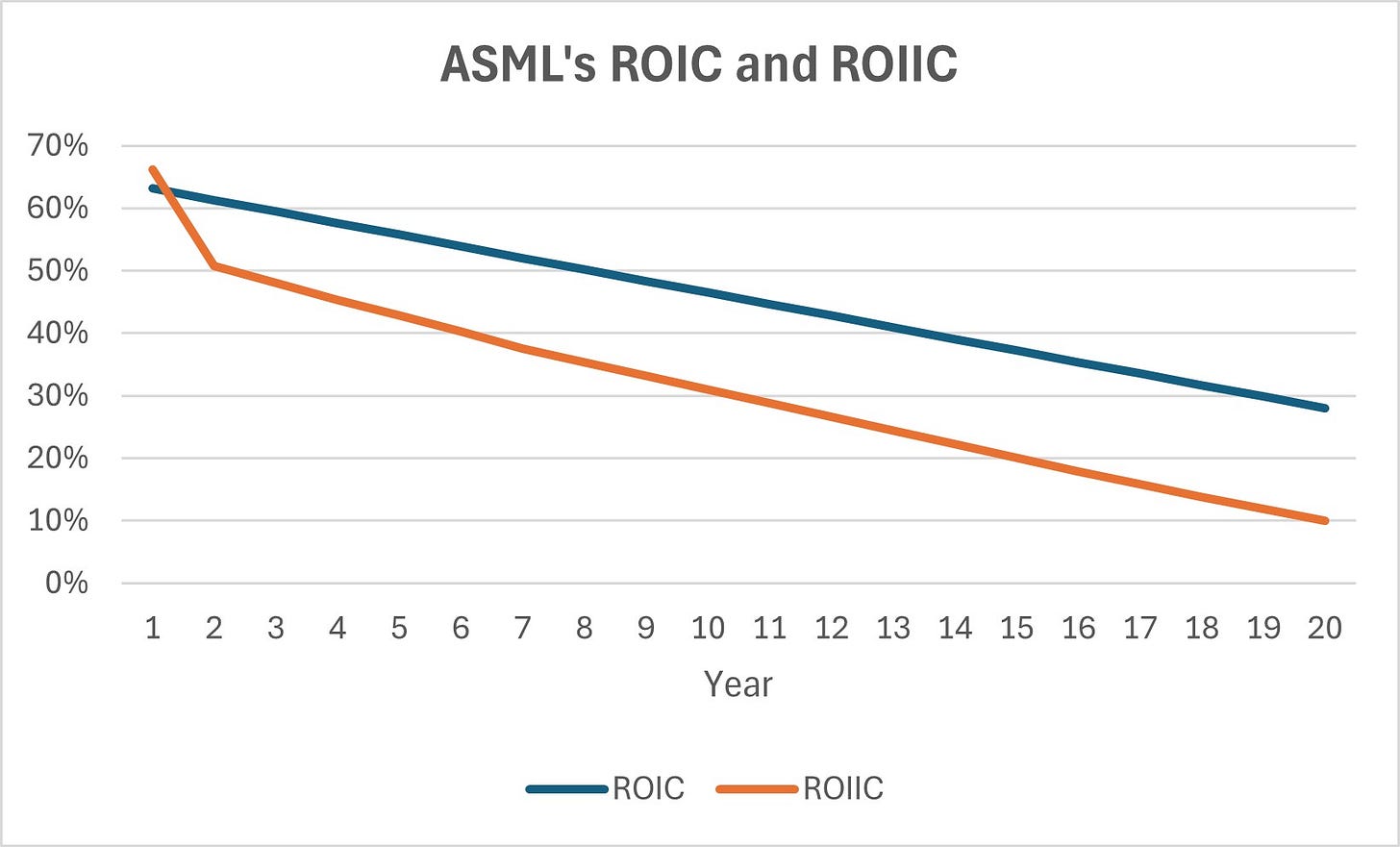

The forecast period should extend until the company’s return on incremental invested capital (ROIIC) falls to the cost of capital—the point when its competitive advantage fades. This period is also known as the competitive advantage period (CAP).

Michael Mauboussin estimates the CAP using the market-implied CAP (MICAP). The method works as follows:

Project free cash flows using steady assumptions for revenue growth, margins, and reinvestment, based on analyst estimates.

Extend the projections until the present value of those cash flows, plus the terminal value, equals the current market cap.

The number of years needed to justify today’s price is the MICAP.

This is still tricky, because in the end, analyst estimates are just that: estimates. Moreover, not every individual investor has access to comprehensive analyst estimates far into the future, so that’s another problem.

In my view, a more intuitive method is to base your CAP on ROIC, the rate of industry change, and barriers to entry.

In ASML’s case, the company consistently earns exceptionally high ROIC while operating in an industry with massive barriers to entry. And although the semiconductor industry evolves rapidly, ASML’s niche—lithography—is far more stable.

A 20-year forecast period for ASML is not unreasonable at all. In fact, even that may be conservative for some firms.

Think of Coca-Cola. A DCF model built in the 1950s—even with a 50-year forecast—wouldn’t have been enough. Truly wide-moat businesses can generate excess returns for generations, and short DCFs miss that.

Using a 20-year model for ASML, we assume that ROIIC fades to the cost of capital (~10%) by year 20, reflecting reversion to the mean.

We begin by projecting revenue, which we assume reaches €52 billion by 2030, then gradually slowing growth to 2.5% by year 20. We also assume operating margin expansion from 32% today to 40% over the period.

Now here’s where it gets interesting.

In the post mentioned earlier about DCF mistakes, I made a DCF model for Costco. There, I manually projected invested capital line-by-line—which is both time-consuming and unnecessary.

A better approach is to project invested capital using ROIC. Start by setting a year 20 ROIC that implies an ROIIC of around 10%, then gradually taper toward that level from the current ROIC. Since we’ve already projected operating income, combining it with ROIC gives us invested capital. From there, we can estimate capex and D&A as a percentage of invested capital—ensuring reinvestment assumptions are economically sound.

This is a fantastic workaround for anyone struggling to properly integrate ROIC into their DCF model.

Buy-In Targets

In markets like today’s, having clear price targets is essential. While I don’t rely on multiples to make buy or sell decisions, building full DCFs for every company on your watchlist can be time-consuming—especially if you want them accurate.

That’s where multiple-based valuation comes in. It’s a great tool for screening your watchlist and narrowing down which companies might actually deserve a deeper DCF analysis.

Once you do decide to build a DCF, don’t overlook the competitive advantage period—and always make sure ROIC is tied into your projections.

Finally, hurdle rates are incredibly useful for setting price targets. For wide-moat businesses, I believe a 10% hurdle rate is reasonable. That means you’d set the discount rate to 10%, and the resulting intrinsic value becomes your buy-in target.

If you’re interested in the ASML model I used for today’s post, you can always send me a message!

In case you missed it:

Disclaimer: the information provided is for informational purposes only and should not be considered as financial advice. I am not a financial advisor, and nothing on this platform should be construed as personalized financial advice. All investment decisions should be made based on your own research.

Hi....Can you send me your ASML model?...Tks for all

Your concept is very close to mine.

But the runway period of ours are differently set up.

KLSE:INFOTEC

Intrinsic Earning Value (Discounting ROIC Model)

= EPS×(1÷1.CPI)×(1-(1÷1.CPI)^ROIC)÷(1-(1÷1.CPI))

= 0.0481×(1÷1.03)×(1-(1÷1.03)^26.16)÷(1-(1÷1.03))

= MYR 0.8633839316

MYR 0.8633839316 itself has incorporated a huge MOS.

ROIC is best to be adjusted with Invested Capital by adding the non-productive Idle Cash if any, by this way, adjusted/justified ROIC will be lowered and the runway period will be reduced.

Idle Cash has no economical value.