How to Value Stocks using Discounted Cash Flow (DCF)

Learn how to value stocks using the discounted cash flow method. Includes a free downloadable Excel template.

Dear reader,

In my most recent Portfolio Letter, I touched on stock valuation, arguing that it isn’t as important as business fundamentals. While I still hold that view, I've come to realize the importance of having a solid valuation framework. This is the second article in a series on broader investing topics, designed to help you grasp key concepts while saving you valuable time.

There’s no shortage of content out there trying to explain valuation—some of it more complicated, some better, some worse. While writing this article, I found The Little Book of Valuation to be of great help. Its author, Aswath Damodaran, is a highly respected figure in finance, and his work is widely regarded.

What is Valuation?

First, it’s essential to differentiate between a stock’s market price and its intrinsic value. The market price is driven by supply and demand—the more demand, the higher the price, and vice versa. More supply (sellers) drives the price down until equilibrium is reached. This is basic economics. In the short term, supply and demand for stocks is influenced by numerous factors like earnings reports, news, and sentiment. But in the long term, the company’s fundamentals—growing profits, cash flows, stock buybacks, and dividends—are what matter.

When valuing stocks, investors attempt to attach a price tag to them. Knowing a stock’s intrinsic value helps us make better decisions, like whether to buy or hold off. In theory, it’s simple: buy when the intrinsic value is higher than the market price. But calculating intrinsic value is tricky and full of uncertainty. It’s essentially an educated guessing game.

Stock valuation is the process of estimating a stock’s intrinsic value to decide whether it’s worth buying.

Discounting

While Damodaran explains two methods of valuation in his book, this article focuses on intrinsic valuation. At its core, a stock’s intrinsic value is based on cash flows. More precisely, the present value of future expected cash flows. This is why valuation is largely guesswork.

What do we mean by present value?

Cash you receive in the future is worth less than the same amount today for a few reasons:

Cash today can be spent or invested to generate more capital, making it more valuable now.

Inflation decreases the purchasing power of future cash. A dollar today buys more than a dollar in the future.

Future cash flows are uncertain and carry risk—there’s no guarantee you’ll receive them.

Because of these factors, we need to discount future cash flows to accurately reflect their present value. Discounting is straightforward and requires three inputs: the future cash flow, the discount rate, and the number of periods (usually years) before you receive the cash.

The discount rate represents the expected return, or what you could’ve earned had you received the cash today. This is also known as the cost of capital, which can be calculated for companies using the Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC). More on that later.

Here’s the formula for discounting cash flows:

For example, let’s say you expect to receive $100 in 10 years, with a discount rate of 10%. The present value of that cash flow would be:

This makes sense intuitively because $38.55 compounded at 10% annually for 10 years would grow to $100. In other words, if the expected return is 10%, and you invest $38.55 today (perhaps in the S&P 500), you’d have $100 in 10 years.

By further breaking down this formula, we learn two key insights:

The further into the future a cash flow is, the less it’s worth today.

The higher the discount rate, the less a future cash flow is worth. This is why the stock market reacts so strongly to changes in interest rates, which influence discount rates.

Now that we understand how to value individual cash flows, the next step is calculating the value of an entire business—or a single stock.

Collecting Inputs

Damodaran outlines four essential inputs for estimating a company’s value:

Current and historical cash flows.

Expected growth in these cash flows during the forecast period.

The cost of capital.

An estimate of the firm’s value at the end of the forecast period, known as the terminal value.

To calculate free cash flow, we can use the following formula:

Let’s take Alphabet (the parent company of Google) as an example. All of the data can be found in the company’s financial statements. Alternatively, websites like Yahoo Finance or Seeking Alpha provide financial information but sourcing it directly from the company’s statements minimizes errors.

First, calculate the after-tax operating income, also known as NOPAT, which you can find in the income statement. I previously explained how to calculate this in my post about ROIC. Next, find depreciation and amortization, as well as any goodwill impairments, which are listed in the cash flow statement.

Then, subtract capital expenditures and acquisitions, but remember to add back any divestments, which can also be found under ‘Investing Activities’ in the cash flow statement. Lastly, subtract changes in net working capital (operating assets and liabilities). These figures can be found in the balance sheet, but this step can be tricky. Instead of looking at the working capital itself, you need to subtract the changes in working capital compared to the prior year. To do this, first calculate the net working capital for the current year, then subtract the previous year’s working capital.

You should gather as much data as possible, looking back as far as you can. For Alphabet, the company’s free cash flow will look something like this:

To make the forecasting easier, I common-sized most of the data and calculated averages. Since predicting figures like changes in net working capital can be challenging, using averages is often the best approach.

Forecasting

Forecasting begins with revenue, where you need to connect the numbers to the company's story. What’s Alphabet’s narrative? While I won’t delve deeply into the company’s prospects, let’s assume it will continue to experience double-digit growth due to secular trends and optionality, though growth may slow as the market saturates. Given that the revenue compound annual growth rate (CAGR) was nearly 20%, we’ll project Google will maintain double-digit growth over the next few years before experiencing a slowdown.

Next, we need to assign operating margins to our forecasted revenue figures. Alphabet’s average operating margin is 24.9%, but the company has been improving its margins in recent years. For our forecast, we’ll assume Alphabet's operating margin gradually rises to 32%. This may still be a conservative estimate, but the goal of this article isn’t to accurately value Alphabet but to illustrate the intrinsic valuation method.

We’ll use the average tax rate, which is around 20%.

For depreciation and amortization, we see a clear trend: it has become a smaller portion of revenue over time. Using the average could lead to an inaccurate estimate. The overall average is 6.1%, but in the last three years, it has been around 4-5%. Therefore, we’ll use the average of those last three years to forecast depreciation and amortization.

For capital expenditures and acquisitions, we will take the average, as there’s no clear upward or downward trend. This is likely a conservative approach, but again, not the main focus of this article.

We’ll do the exact same for changes in net working capital.

With all of this in place, we now have a solid forecast of Alphabet’s future free cash flows.

Cost of Capital

The next step in the valuation process is to discount the free cash flows to their present value, which requires a discount rate. For companies, this discount rate can be calculated using the Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC) formula. A company is funded by both debt and equity, each with its associated costs. By combining these costs, we arrive at the WACC. The formula is as follows:

The formula looks complicated but is straightforward: you multiply the proportion of equity by the cost of equity and do the same for debt.

The cost of equity is typically calculated using the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM).

Provided below is an Excel sheet that explains some of the inputs required for calculating WACC, so don’t worry if it seems complex.

Based on my calculations and assumptions, Alphabet’s WACC is approximately 10.1%. This is the rate I’ll use to discount each cash flow to its present value.

Terminal Value

We now have the present value of Alphabet’s free cash flows for the next 10 years. However, it’s likely that Alphabet will continue to exist and generate cash flows beyond this period. Since projecting cash flows far into the future is unrealistic and increasingly challenging, we use another method to account for the time beyond those 10 years: the terminal value. This value captures the long-term potential of the company while keeping the discounted cash flow valuation method practical.

We calculate the terminal value using the following formula:

TGR stands for the terminal growth rate, which typically reflects the growth rate of the overall economy in which the company operates. For U.S. companies like Alphabet, this is generally around 2-3%.

Once we have the terminal value, we need to discount it back to present value, just as we did with the cash flows.

Everything Together

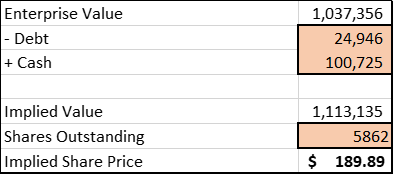

We sum the present value of all cash flows and the present value of the terminal value to arrive at the enterprise value. Next, we add the current cash position and subtract the debt to get the company’s implied value. Finally, we divide this implied value by the number of shares outstanding to determine the implied share price.

Want to take a look at the entire discounted cash flow model and use it to value companies yourself? Download here for free:

We now have an estimated intrinsic value for the stock. However, there are some important truths to keep in mind, as Damodaran highlights:

All valuations are biased. Valuing a company inherently involves biases. Before you even start, you likely have an opinion about the company, whether positive or negative. The process of selecting a company to value isn’t random; it often stems from prior knowledge or discussions. After completing your valuation, if the result isn’t what you hoped for, it’s tempting to engage in what Damodaran calls “post-valuation garnishing,” where you adjust your estimated value by applying premiums or discounts. To counteract this, Damodaran recommends writing down all your biases before you begin.

All valuations are wrong. Yes, you read that correctly. The valuation we just conducted for Alphabet is terribly wrong. There are always estimation errors; for instance, my model projects Alphabet will generate $661 billion in revenue by 2033, which is highly improbable. Besides estimation errors, there’s always the chance that your predictions are hopelessly wrong. There’s a chance Alphabet will completely fail, and maybe their revenue will stagnate until 2033.

The key takeaway is to acknowledge that your valuation will be wrong, but to still do it. Every investor faces the same uncertainties, and the goal is to be less wrong than others.

The simpler, the better. Damodaran points out that valuations have become increasingly complex over the years, yet more detail often leads to greater potential for error and more complicated models. When valuing a stock, aim to use the simplest model possible. In this case, less is more.

Conclusion

The discounted cash flow valuation is arguably the most effective method for determining a company's intrinsic value. While the process may seem daunting at first, I hope this article and the accompanying Excel sheet have made it easier.

If you have any questions about intrinsic valuation, feel free to send me a direct message on Substack or reply to this email.

While discounted cash flow is a vital component of the valuation framework I’m developing, there’s more to explore. I’ll be discussing other valuation methods in a future post.

Disclaimer: the information provided is for informational purposes only and should not be considered as financial advice. I am not a financial advisor, and nothing on this platform should be construed as personalized financial advice. All investment decisions should be made based on your own research.

Thx, what is your meaning/experience with inverse (reverse) DCF?

Thanks.