Understanding Return on Invested Capital (ROIC)

ROIC is arguably the most critical factor for long-term investors. Learn how it works, from interpretation and calculations to effective analysis.

Dear reader,

Welcome to a new format of Summit Stocks. Besides in-depth deep dives on the world’s best companies that you’ve come to expect from me, you’ll now also receive valuable articles on broader investing topics. By exploring books, letters, articles, and other essential media for investors, I’ll help you navigate key concepts while saving you valuable time.

At its core, long-term investing is about finding companies that can sustain growth while delivering high returns on capital—and holding onto them. That’s why I’ll be diving into the fundamental investing principle of Return on Invested Capital (ROIC) by exploring the article Counterpoint Global Insights: Return on Invested Capital by Micheal Mauboussin and Dan Callahan.

What is ROIC?

ROIC measures how efficiently a company uses its capital to generate profits. It calculates the return a company earns on the money invested in its operations.

The formula for ROIC is simple: After-tax operating profits divided by operating assets, which include working capital, property, plant, equipment, intangibles, and goodwill. We’ll go into more detail later.

ROIC’s counterpart is the cost of capital, also referred to as the opportunity cost of capital, required return, or discount rate. Typically, the cost of capital is below 10%, which is the return you might expect by investing in the stock market via an index like the S&P 500. This is why it’s called an "opportunity cost"—it's the next-best alternative. While the Weighted Average Cost of Capital (WACC) can be used for more precise calculations for specific companies, knowing that a company's cost of capital usually doesn’t exceed 10% is sufficient.

For a company to create value, its ROIC must exceed its cost of capital. The spread—the difference between ROIC and cost of capital—must be positive for growth to be beneficial. Let’s break this down with a simple example:

Company A has the following metrics:

ROIC: 15%

Cost of Capital: 10%

Invested Capital: $100 million

Profit (NOPAT): $15 million (calculated as $100 million * 15%)

Company A decides to grow by investing an additional $20 million, increasing its total invested capital to $120 million. After this investment, Company A's profit increases to $18 million (calculated as $120 million * 15%), a $3 million rise. The cost of financing the additional $20 million is $2 million (calculated as $20 million * 10%). This is what we as investors would have earned had we invested in the stock market. As a result, Company A creates $1 million in value ($3 million increase in profit minus $2 million cost of capital).

Company B has the following metrics:

ROIC: 5%

Cost of Capital: 10%

Invested Capital: $100 million

Profit (NOPAT): $5 million (calculated as $100 million * 5%)

Observing Company A’s success, Company B decides to expand by investing an additional $20 million, raising total invested capital to $120 million. Its profit increases to $6 million, a $1 million rise. However, the cost of capital for the additional $20 million is still $2 million. In this case, Company B has destroyed value, as the $1 million profit increase is less than the $2 million cost of capital. It would have been more beneficial to invest the money elsewhere or pay it out as dividends, such that shareholders can allocate the capital themselves.

The key takeaway from the above example is this: Earnings growth doesn’t necessarily equal shareholder value. The spread between ROIC and the cost of capital is what determines value creation. In this case, Company B should focus on operating more efficiently rather than growing.

At first, the concept may seem confusing—it certainly was for me. Why wouldn't higher profits automatically lead to greater shareholder value? But it's true: more profit doesn't always translate to more value for shareholders.

How to Calculate ROIC

Let’s take a closer look at how ROIC is calculated and how to analyze it effectively.

As previously mentioned, ROIC is calculated by dividing NOPAT by invested capital, which includes operating assets such as working capital, property, plant, equipment, intangibles, and goodwill.

Let’s begin with the numerator, NOPAT (Net Operating Profit After Taxes). Why not use net profit or operating income instead? Mauboussin and Callahan argue that NOPAT is a better metric because it eliminates the impact of a company's capital structure, allowing for better comparisons between firms.

“NOPAT, the numerator of the ROIC calculation, is the cash earnings a company would have if it had no debt or excess cash. That means that NOPAT, unlike earnings, is the same whether a company is financed with all equity or if it has a lot of debt. Removing the issue of capital structure allows for effective comparison between businesses.”

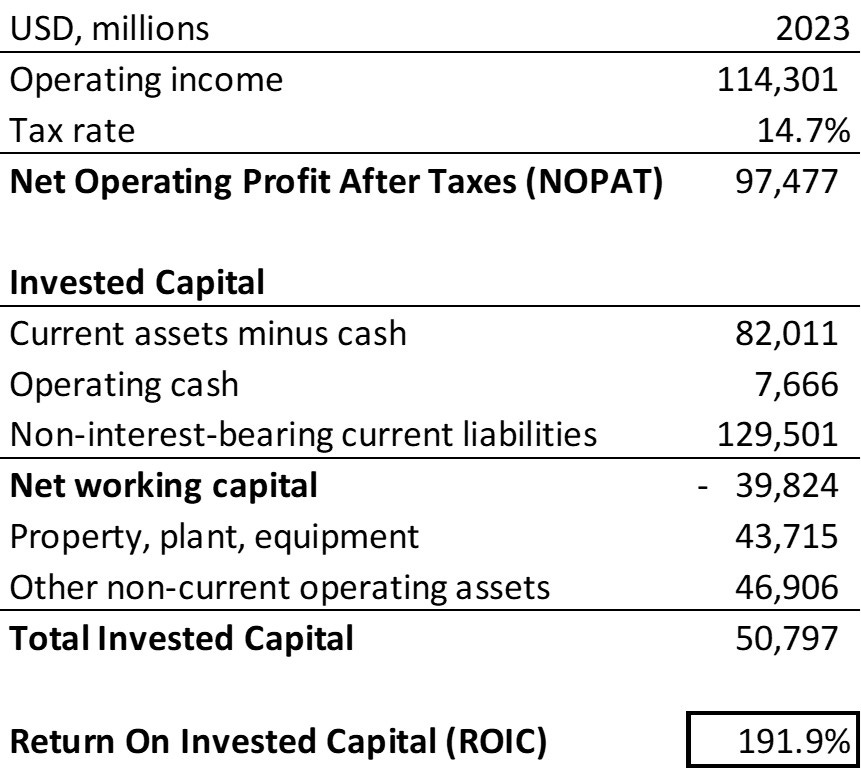

To calculate NOPAT, start with operating income (EBIT) and subtract the effective tax rate as if it were applied to EBIT. Let’s use a real-life example:

In FY2023, Apple’s operating income was $114.3 billion.

Its effective tax rate was 14.7%.

Therefore, Apple’s NOPAT was $97.5 billion ($114.3 billion * (1 - 14.7%)).

Mauboussin and Callahan also suggest adding back amortization from acquired intangible assets to NOPAT, but in my experience, this step is both complicated and insignificant, as it typically has little impact on the overall outcome.

Now, let’s move to the denominator: invested capital, which represents the net assets a company needs to generate NOPAT. These are the operating assets—factories, vehicles, software, etc.—that are required for running the business. Invested capital is calculated by adding working capital to non-current operating assets.

Working capital is calculated by subtracting non-interest-bearing current liabilities from current assets, excluding excess cash and marketable securities. While that may sound complicated, it’s simpler than it appears:

Non-interest-bearing current liabilities include all current liabilities except for debt.

Current assets are the typical current assets, but with one key adjustment: in calculating working capital, we exclude excess cash and marketable securities—cash that isn’t needed for day-to-day operations. Many companies hold large amounts of cash, but only a small portion is used for operating needs.

Take Alphabet—Google’s parent company—which holds just over $100 billion in cash and equivalents, far more than it requires for daily operations. As a rule of thumb, 2% of revenue can be considered necessary operating cash. Any amount beyond that should be subtracted from current assets.

We’ll continue using Apple as a real-life example:

Apple holds significantly more cash than it needs. Using 2% of revenue as a guide, its operating cash would be $7.7 billion (2% of $383.3 billion), leaving total adjusted current assets at $89.7 billion ($143.6 billion minus $30 billion, minus $31.6 billion, plus $7.7 billion). Apple’s non-interest-bearing current liabilities amount to $129.5 billion ($145.3 billion minus $6 billion, minus $9.8 billion).

Thus, Apple’s working capital is negative $39.8 billion, meaning its liabilities exceed its current assets. Mauboussin and Callahan explain that such companies have a negative cash conversion cycle, meaning they collect payments before needing to pay suppliers. Suppliers essentially become a source of financing, which often indicates strong bargaining power over suppliers and operational efficiency.

Apple’s cash conversion cycle is -68, meaning it collects payments 68 days before paying its suppliers.

Moving on, Apple’s non-current operating assets include $43.7 billion in property, plant, and equipment, along with $46.9 billion in other non-current assets. While the total for other non-current assets is $64.8 billion, $17.9 billion of that consists of deferred tax assets, as can be found in Apple’s financial statements notes. Since Apple doesn't specify the details of its other non-current assets, we must include them all, though they likely consist of intangible assets and goodwill. However, the exact breakdown remains unclear.

Based on this data, we can compute Apple’s ROIC for 2023:

Apple’s ROIC is exceptionally high, driven by its negative working capital and relatively low non-current assets. While high ROIC is generally a positive indicator, an excessively high figure can be a red flag, possibly signaling under-investment, unsustainably high profit margins, or market saturation. Apple is an extremely strong company, but such high returns may not be sustainable in the long term.

You should now be able to calculate ROIC on your own. One final note:

It’s better to use average invested capital rather than year-end figures, as I did for Apple. For example, when calculating ROIC for 2023, you would first calculate NOPAT for the year. Then, calculate invested capital at both the beginning and end of the year (i.e., December 31, 2022, and December 31, 2023), and take the average. You could even take it one step further, calculating invested capital on a quarterly basis throughout the year and taking the average, though that might be too time-consuming.

How to Analyze ROIC

As mentioned before, ROIC must be consistently higher than the cost of capital to create value. I suggest using a 15% hurdle rate—any company with ROIC below this level should typically be ignored. Exceptions can be made for high-quality companies with temporarily low ROIC due to high investments, such as Amazon’s 2022-2023 period.

A high ROIC is important, but consistency is key. A business that delivers stable, predictable ROIC is more attractive than one with fluctuating returns. This is why you should calculate ROIC over at least five years to see if there’s a stable trend or, even better, a positive one.

Lastly, keep in mind the concept of reversion to the mean: high ROICs tend to drift lower over time, and very low ROICs tend to improve. The best companies maintain their high ROIC through strong competitive advantages.

Conclusion

ROIC is a vital metric for investors. For a company to create value, its ROIC must exceed its cost of capital. While calculating ROIC is straightforward, you need to be precise to avoid misleading results. For further insights, I highly recommend reading the full article by Mauboussin and Callahan:

I may write a follow-up episode that covers the remainder of the article (because there’s still a lot to explore), but that’s for the future.

Disclaimer: the information provided is for informational purposes only and should not be considered as financial advice. I am not a financial advisor, and nothing on this platform should be construed as personalized financial advice. All investment decisions should be made based on your own research.

helpful cheers!