FICO: The Business Behind Your Credit Score

A deep dive into the most important credit scoring company

Dear reader,

Welcome back to another deep dive into a wonderful company.

Today, we’re exploring Fair Isaac Corporation, better known as FICO—a leading provider of credit scores and software solutions. In this article, we’ll uncover why credit scores exist and how they came to exist in the first place. Additionally, we’ll explore FICO’s business model, how it generates returns on capital, and what the future holds for the company. Lastly, we’ll evaluate whether FICO is a compelling investment opportunity.

Table of Contents

1. FICO’s History

1.1 Credit Scores

1.2 History of Credit Reporting

1.3 Fair, Isaac and Company

2. FICO’s Business

2.1 How FICO Makes Money

2.2 FICO’s Moat

2.3 Key Financials

2.4 Future Outlook

2.5 Management

2.6 Risks

3. Conclusion

1. FICO’s History

1.1 Credit Scores

Before diving into FICO’s history, it’s important to understand credit scores—their purpose, origins, and evolution. These factors are key to understanding FICO’s role and business.

A credit score is a numerical representation of an individual’s creditworthiness, used by lenders to assess the risk of extending a loan. Calculated using algorithms and data from credit reporting agencies, FICO’s credit scores typically range from 300 to 850, with higher scores indicating lower risk. The score is typically based on factors such as payment history, amounts owed, length of credit history, and types of credit used.

Credit scores offer numerous benefits to lenders:

Standardized Assessment: Credit scores provide a consistent measure of creditworthiness, allowing lenders to streamline risk evaluation, reduce time, and lower costs.

Enhanced Product Offerings: Lenders can offer better terms—like lower interest rates—for individuals with high credit scores, leading to greater borrower satisfaction.

Fraud Prevention: Credit scores can help detect unusual activity, enabling lenders to take preventive action when scores change unexpectedly.

Credit scores are also beneficial to borrowers:

Access to Credit: A high score increases the likelihood of loan approval and gives borrowers more negotiating power.

Cost Savings: Higher scores typically result in lower interest rates and better loan terms, such as longer repayment periods or reduced fees.

Financial Awareness: Credit scores encourage individuals to monitor their financial habits, leading to better overall financial health.

With this understanding, let's take a look at the origins of credit scores and FICO.

1.2 History of Credit Reporting

The roots of credit scores trace back to the 19th century, a time when debtors could easily avoid repayment, often by assuming false identities or migrating to a different region. As a result, lenders frequently found it challenging to assess a borrower’s creditworthiness. With the rise of business transactions in the first half of the century, the need for a more reliable system of credit rating became even more apparent.

In 1841, American merchant and abolitionist Lewis Tappan established the Mercantile Agency, the first agency dedicated to rating commercial credit, which focused on businesses rather than individuals.

However, the Mercantile Agency's method of assessing borrowers was inherently subjective, given the technological limitations of the time. Additionally, early reports reflected biases related to discrimination, gender, and social reputation. The agency operated by gathering information from correspondents across the country, who reported on debtors and collected data in extensive ledgers. These correspondents all had varying methods of assessing creditworthiness, each influenced by their own prejudices and imperfections. Businesses could subscribe to the Mercantile Agency to access this compiled information.

Despite its pioneering role, the reports produced by the Mercantile Agency were inconsistent and overly subjective. Subscribers of the Mercantile Agency and those of its rival Bradstreet Company increasingly demanded a simpler method of credit reporting.

In 1864, the Mercantile Agency, then renamed R.G. Dun & Co, introduced an alphanumeric system for tracking the creditworthiness of companies, which would remain in use until the 20th century.

The 20th century marked the rise of consumer credit as household incomes increased and more people aspired to a middle-class lifestyle. Efficient factories produced affordable goods, such as automobiles (like the Ford Model T), washing machines, refrigerators, and furniture. These products were often purchased on credit, which meant consumers, not just businesses, now needed to be evaluated for creditworthiness.

In 1899, the Retail Credit Company (RCC) was founded to collect data on creditworthy consumers. RCC later became Equifax, one of the three major credit bureaus in the U.S., which today provides data used to generate FICO Scores.

By the 1950s, credit had become a widespread way for consumers to make purchases. With multiple credit accounts at various merchants, this era laid the groundwork for companies like Visa, MasterCard, and American Express to thrive.

1.3 Fair, Isaac and Company

Fair, Isaac and Company was founded in 1956 by engineer Bill Fair and mathematician Earl Isaac with the goal of using mathematical models and algorithms to help businesses make objective decisions, initially focusing on credit risk assessment.

While credit scoring had significantly evolved from its early days at the Mercantile Agency, it remained flawed. Loan approvals often depended on personal relationships with bankers, judgments were still based on character, there was no standardized system, and credit reporting was manual work.

Fair and Isaac aimed to address these issues. However, in its early years, the financial industry was slow to adopt FICO’s objective, mathematical methods.

A major turning point came with the Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA) of 1970, which promoted the accuracy, fairness, and privacy of consumer information in credit reports. Previously, credit reports included personal details like character, habits, and health. With the FCRA, such information became private and could no longer be used to assess creditworthiness.

While the FCRA laid the groundwork for standardized credit reporting, it took another 19 years for FICO to fully capitalize on this. After the legislation, FICO’s models began to gain traction with the three major credit bureaus—Equifax, Experian, and TransUnion—but widespread use of FICO’s credit scores remained limited.

In 1989, FICO introduced the FICO Score, a standardized numerical score to assess an individual's credit risk. The FICO Score differed from older models in several critical ways:

Standardization: Earlier models were custom-made for individual lenders, leading to inefficiency, confusion for borrowers, and challenges in benchmarking. The FICO Score provided a uniform system.

Numerical Simplicity: Older models often relied on qualitative assessments or internal metrics, while the FICO Score used a clear numerical range.

Sophisticated Approach: The FICO Score used more advanced mathematical techniques compared to simpler earlier methods.

Transparency: The 1989 FICO Score offered better access and clarity, making it easier for borrowers to understand their credit score.

The 1989 FICO Score was quickly adopted across various types of credit, including mortgages, car loans, credit cards, and personal loans. Today, it is the dominant credit score in the U.S., used by more than 90% of U.S. lenders.

2. FICO’s Business

2.1 How FICO Makes Money

Today, FICO generates revenue through its credit scores, but also by offering software to businesses through a SaaS model. The company distinguishes its business into two operating segments:

Scores: FICO’s Scores segment includes B2B and B2C solutions, with the FICO Score being the standard measure of consumer credit risk in the U.S. Nearly all major banks, credit card issuers, mortgage lenders, and auto loan providers use FICO to assess lending risks and approve credit applications.

The FICO Score ranges from 300 to 850 and is generated using proprietary algorithms based on data from Experian, TransUnion, and Equifax. A higher score indicates lower credit risk, increasing the chances of loan approval and securing better interest rates and loan terms. It benefits both lenders and borrowers while remaining cost-effective.

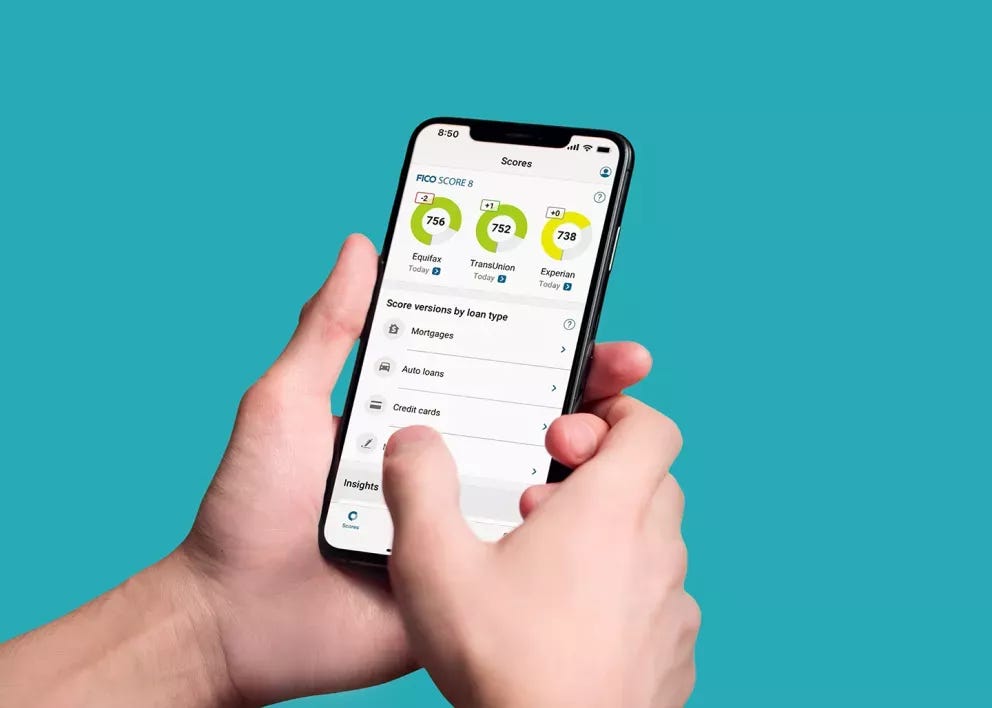

Revenue for the Scores segment comes from licensing fees paid by financial institutions, either per-score or through subscription models, as well as direct-to-consumer sales on myFICO.com. Financial institutions purchase FICO Scores to assess the creditworthiness of potential borrowers, with investment research firm Morningstar estimating the average cost at about $0.05 per score.

Consumers can also obtain scores through subscriptions (starting at $19.95 per month) or one-time purchases. Additional revenue streams include partnerships with credit bureaus and custom scoring solutions.

In FY2023, the Scores segment generated $774 million in revenue, accounting for 51% of total revenue, and produced $619 million in operating income, representing 74% of operating income (excluding unallocated corporate expenses). This underscores that the Scores segment is not only high margin but also the company's most critical segment.

Software: FICO’s second segment is the Software segment. In addition to credit scores, FICO offers software solutions which mostly address customer engagement, onboarding, servicing and management, and fraud protection, through the use of analytics and data-decisioning technology. FICO’s software helps businesses automate, improve, and connect decisions across their enterprise.

The company’s various software offerings are especially focused on four analytic domains: Predictive modeling, decision analysis and optimization, transaction profiling, and customer data integration.

Importantly, FICO also offers the FICO Platform, a centralized, scalable platform which includes almost all of FICO’s software offerings in one package. Additionally, customers are able to add their own analytic capabilities and configure their own solutions onto the platform. The company is investing to be able to run all its software solutions natively on FICO Platform. This is because the FICO Platform has higher retention rates than the non-platform solutions.

Another key takeaway which we can gather by looking at the company’s retention rates: It’s been consistently well above 100%, indicating that FICO generates more revenue from existing and new customers than the revenue it loses from customer churn. Likely reasons can be upselling and cross-selling, price increases, and a low churn rate.

In FY23, the Software segment generated $740 million in revenue, representing 49% of total revenue, with operating income of $241 million, representing 26% of operating income excluding unallocated corporate expenses.

2.2 FICO’s Moat

FICO’s moat is primarily driven by its network effect, with intangible assets and switching costs as secondary sources.

The FICO Score, as the standard measure of credit risk in the U.S., is the strongest part of FICO’s business. It has been widely adopted by multiple key stakeholders—banks, borrowers, investors, and regulators—creating significant barriers to entry for competitors. Lenders heavily rely on FICO Scores when making lending decisions, which compels consumers to monitor and maintain their scores to access affordable credit. This mutual reliance keeps the FICO Score relevant and reinforces its position in the market.

Moreover, the more lenders and consumers use FICO Scores, the more data FICO collects, enabling it to continually refine and improve its scoring models. This increased accuracy attracts even more users, strengthening the network.

The FICO Score is so deeply embedded in the credit industry that it has become nearly irreplaceable. The cost-benefit dynamic is another factor that bolsters the company’s market-leading position. For example, lenders pay only about $0.05 per FICO Score, a minimal cost compared to the value it provides. Even for consumers, purchasing a FICO Score for around $20 can be highly advantageous. For example, a $20 score that leads to lower mortgage rates easily justifies the expense. This also gives the company significant pricing power.

Beyond the network effect, FICO benefits from intangible assets, particularly its brand. In the U.S., the FICO Score is virtually synonymous with credit scores. When consumers or lenders think about creditworthiness, they often think of FICO first, creating an extra layer of trust and familiarity.

Lastly, FICO’s Software business poses switching costs, as is typical for software solutions. Once FICO’s software is integrated into a company’s infrastructure, replacing it becomes time-consuming, costly, and risky. The company’s high retention rates in this segment underscore these switching costs.

In summary, FICO enjoys a wide moat, reinforced by its deeply entrenched FICO Score, strong brand recognition, and software-related switching costs.

2.3 Key Financials

FICO has been showing consistent revenue growth at sustainable rates over the past years. Its compound annual growth rate since FY2014 is 8%.

Importantly, however, growth can be largely attributed to the Scores segment, with the Software segment seeing relatively little growth. As seen in the exhibit below, Scores revenue has more than doubled since FY2019, while the Software segment has seen very little growth.

While I’d obviously prefer to see Software grow as well, this shift in the company’s product mix does have an advantage: margins on the Scores segment are significantly higher than FICO’s Software margins. Since FY2014, gross margins have improved from 68% to 79% and operating margins have significantly improved from 21% to 43%. I believe this is mostly thanks to the company’s shift in product mix, as well as operational efficiencies and pricing power.

The company is clearly very profitable, which is further reflected in its net profit and free cash flow. Free cash flow has been consistently higher than net income, but that’s due to the company’s stock-based compensation, which has been increasing in absolute terms but also as a percentage of revenue. This is something to keep an eye on. In FY2014, stock-based compensation equaled 5% of revenue, while it’s grown to 8% in FY2023.

Stock-based compensation aside, the company has shown strong double-digit growth over the years for both net income and free cash flow. It will be difficult, however, to continue such growth with lower revenue growth, as margins can only grow so much, especially when considering that gross margins are already nearing 80%.

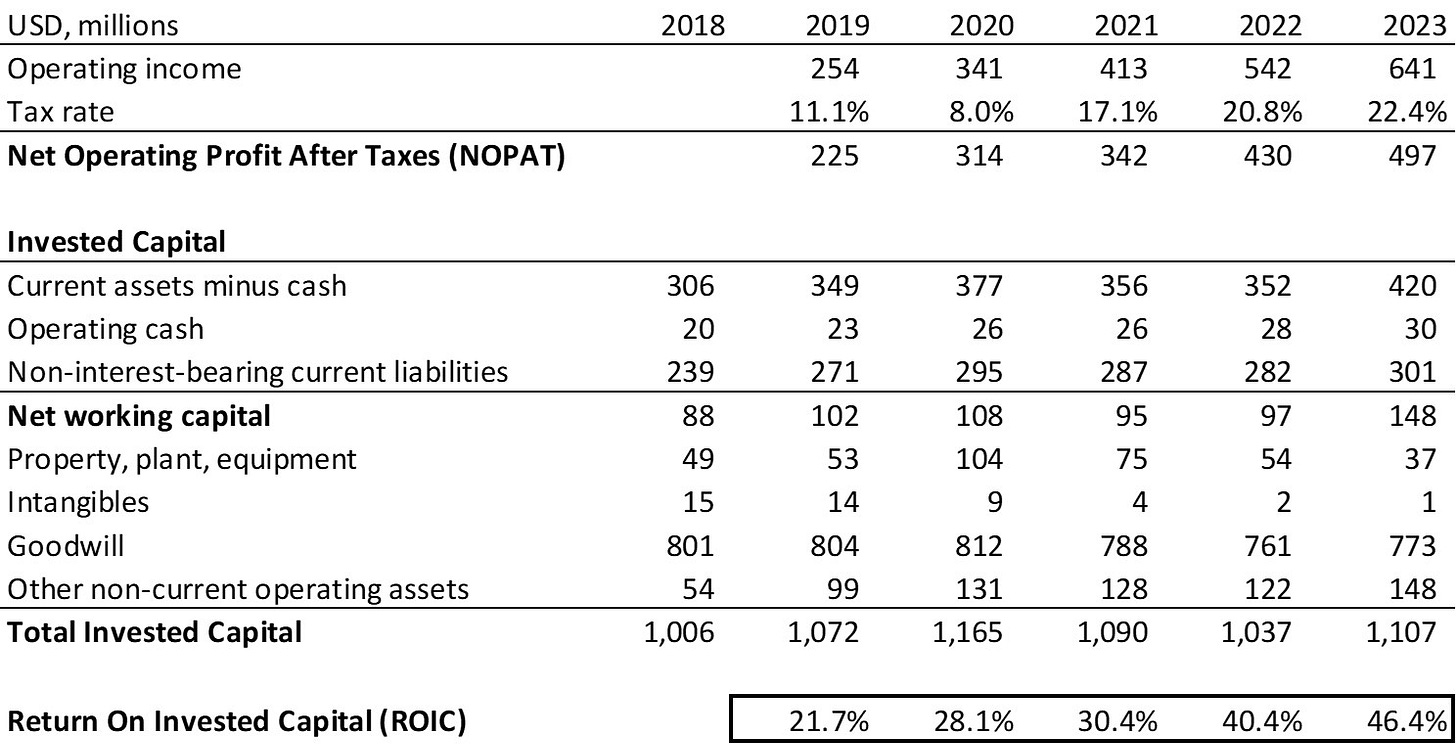

Next, FICO’s Return on Invested Capital (ROIC) has been increasingly strong, thanks to significant increases in operating income while invested capital has stayed relatively flat. This proves that FICO’s business model is highly scalable; the company doesn’t need to invest much to generate additional revenue and income.

Finally, FICO’s balance sheet is a bit weaker than one might expect from such a strong business, yet still manageable. The company holds $156 million in cash and equivalents against $2.2 billion in total debt. The vast majority of the company’s debt—$2.1 billion—is long term debt. Nevertheless, the company holds a net debt position of $2 billion, which equates to a net debt to free cash flow ratio of 3.55, meaning it would take the company over three and a half years to pay down all its debt using its cash position and incoming free cash flow. That is, assuming free cash flow stays consistent. Moreover, the company’s interest cover ratio is 7, meaning its operating income is 7 times higher than its interest expense.

While manageable, I’d prefer to see a more robust balance sheet typically.

2.4 Future Outlook

The global acceptance and use of credit, especially in the U.S., provide FICO with a long runway for growth. Once considered taboo, attitudes toward debt have shifted, and borrowing has become more socially acceptable. Innovations like 'buy now, pay later' and micro-lending have further normalized borrowing in modern society.

One thing is clear: debt is very unlikely to go out of style anytime soon, strengthening FICO’s position as credit scoring leader. As the credit industry continues to grow, so will FICO. Whether it is mortgages, auto loans, credit cards, or personal loans, FICO benefits. The company should even benefit from a rise in demand for credit globally, particularly in emerging markets.

However, there are some worries as a (potential) FICO investor. As mentioned earlier, FICO’s profit and cash flows have grown significantly faster than its revenue in recent years, driven by margin expansion. While this has been an effective growth strategy, it is finite. As the company’s margins reach higher levels, sustaining the same pace of growth will become increasingly difficult. As a result, I expect future profit and cash flow growth to more closely align with revenue growth.

2.5 Management

FICO’s CEO Will Lansing has been at the company for 18 years. He initially joined as a board member in 2006 and became CEO in 2012. His extensive experience makes him well-equipped to lead the business, as evidenced by FICO’s extraordinary results under his leadership since 2012.

Lansing currently holds 468,729 FICO shares, representing a 1.89% stake in the company. His position is valued at nearly $900 million as of this writing, which aligns his interests with those of other shareholders. In 2023, Lansing received $66 million in compensation, a substantial increase compared to the $19 million he earned in both 2022 and 2021. However, his stake in the company still far outweighs his annual compensation, further aligning his long-term incentives with shareholder value.

FICO’s capital allocation strategy is exemplary. Rather than paying dividends, the company focuses on share buybacks. While the current share price is considered high by many, FICO tends to repurchase shares when the price is lower. For instance, the company bought back significantly more shares in 2021 and 2022, before the stock price surged. The company allocates little towards capital expenditures, which makes sense considering the capital-light nature of the business. Finally, the company hasn’t meddled in significant acquisitions. The emphasis is very clearly on share repurchases, which is a better way of returning profits to shareholders than dividends if done right.

2.6 Risks

FICO faces multiple risks, some bigger than others. These are the company’s biggest risks from an investor’s perspective:

Regulatory Challenges: Changes in credit reporting regulations could affect FICO’s business in a negative way. Especially when considering that the credit industry is a critical industry, it might face regulatory problems in the future.

Disruption: Disruption is often a key risk for companies, including FICO. As more fintech companies and digital financial services appear, traditional creditworthiness measures might become less relevant.

Economic Cyclicality: FICO’s performance is tied to the overall economy. In economic booms, there’s more lending activity, and vice versa.

3. Conclusion

FICO remains a cornerstone of the credit industry, with a business model that generates exceptionally high returns on capital. As credit becomes more widely accepted globally, and new forms of lending such as BNPL (Buy Now, Pay Later) gain popularity, FICO stands to benefit from these trends and grow its revenue. However, the key question is how much further the company can expand its margins. While there may be some room for additional operating margin growth, I anticipate that profit growth will more likely align with revenue growth in the medium to long term.

FICO is clearly an exceptional business, and its stock price is very demanding. As of this writing, the forward P/E ratio for 2025 is 67. In my view, it's difficult to justify such a premium, so I will keep the stock on my watchlist until the valuation becomes more reasonable.

Disclaimer: the information provided is for informational purposes only and should not be considered as financial advice. I am not a financial advisor, and nothing on this platform should be construed as personalized financial advice. All investment decisions should be made based on your own research.

Thoughts after the recent sell-off? Fears overblown or thesis is over? Of course stock is still expensive but bounce back possible if regulatory pressures ease