Valuation: Back to Basics, Starting With Expectations

Market expectations, moats, and decision-making

Over the past year or so, I’ve covered the full spectrum of stock valuation across many different articles: DCFs and reverse DCFs, ROIC and reinvestment rates, common modeling errors, and the nuances of market expectations, probability, and valuation ranges.

While I currently use a mix of models, the process can easily become overly complicated and opaque. Lately, I find myself straying from the core question: What is value, actually, and how does it differ from fundamentals?

Valuation is more art than science, but we can still rely on frameworks to keep things simple. Today, I’m going back to basics, based on Michael Mauboussin’s work at The Consilient Observer. Given the current volatility in the market, the timing feels right.

The Epistemology of Value

Epistemology is a very fancy word, but it boils down to the difference between a justified belief and an opinion.

That distinction matters in investing. You need to understand the gap between what you think will happen and what the market believes will happen. Mauboussin likes to explain this with a horse-racing analogy. Everyone knows which horse is most likely to win, which means the odds are terrible. You can be right about the winner and still earn nothing.

Steven Crist, a renowned figure in the horse-racing niche, said the following:

“This is the way we all have been conditioned to think: Find the winner, then bet. Know your horses and the money will take care of itself. Stare at the past performances long enough and the winner will jump off the page.

The problem is that we’re asking the wrong question. The issue is not which horse in the race is the most likely winner, but which horse or horses are offering odds that exceed their actual chances of victory.

This may sound elementary, and many players may think they are following this principle, but few actually do. Under this mindset, everything but the odds fades from view. There is no such thing as ‘liking’ a horse to win a race, only an attractive discrepancy between his chances and his price.”

In horse-racing, the odds aren’t set by a bookmaker, but by the crowd. The “price” of a horse is simply the payout if it wins, and that payout moves inversely with the crowd’s confidence. A horse with a 90% chance of winning might pay out only $2.10 on a $2 bet. A horse with a 10% chance might pay out $20. Strong fundamentals with high expectations pay little. Strong fundamentals with low expectations pay a lot.

The intelligent bettor, just like the intelligent investor, is not trying to identify the fastest horse. The goal is to find situations where the horse’s true probability of winning is higher than the probability implied by the odds.

The best company can make for a mediocre investment if the stock price already assumes greatness. A troubled company can be a spectacular investment if the market has priced in bankruptcy. The point isn’t just to pick winners. The point is to find mispriced outcomes.

A stock price is ultimately the market’s collective opinion about a stream of future cash flows. If XYZ trades at $100, that price reflects a consensus about how high those cash flows will be and how long they will last.

The intrinsic value of any financial asset is the present value of the cash it will generate over its life. The math is straightforward, but the inputs depend on predicting the future, which is what makes investing more art than science.

In practice, we typically project a stream of cash flows for five to ten years, add a terminal value, and discount everything back to today. If the resulting intrinsic value exceeds the current market price, the stock is undervalued.

But forecasting places the burden on the investor’s ability to predict the future, and leaves him with a false sense of precision. Many investors see this and abandon DCFs altogether. But shifting to multiples is no solution. A P/E ratio is just a compressed DCF, only with your assumptions implicit. Targeting a P/E of 25 without knowing what it implies is worse than building a DCF with explicit assumptions.

Mauboussin suggests a better approach: flip the process and let the market reveal what it believes. This is Expectations Investing.

Inverting the Forecasting Problem

If you’ve been investing for some time, reverse DCFs should be familiar to you. Instead of forecasting to find value, you start with the stock price—the only fixed number—and extract the expectations embedded within it.

You stop asking “What is this stock worth?” and start asking “What performance must this company deliver to justify this price?”

You can do this by solving for free cash flow growth, or by isolating the five value drivers and solving for each one of them:

Sales growth

Operating margin

Investment rate

Cost of capital

Competitive advantage period (CAP)

Once you build a market-implied model, you test whether the embedded assumptions make sense using common sense, fundamental research, and base rates.

For example, say you want to understand what revenue growth rate is implied in Adobe’s current price. You build the DCF, fill in the four known drivers using conservative inputs and near-term analyst estimates, and solve for the revenue growth rate that matches the market price.

Our reverse DCF in Summit’s Analytics currently solves only for free cash flow growth, but we’re working on expanding it. This part of the process is too important to simplify away.

Moats and Longevity

Valuation and competitive analysis are inseparable. Without understanding a company’s competitive advantages and market position, you can’t judge the sustainability of value creation.

Two dimensions matter:

Magnitude: how wide the spread between ROIC and WACC is

Longevity: how long that spread stays positive before reverting to the mean

The CAP is the period during which ROIC exceeds WACC. You can estimate a market-implied CAP by extending cash flows until the model price equals the market price. I do find this imperfect—you often have to assume analyst estimates persist longer than they should—but even a rough estimate is informative.

If the market implies a five-year CAP, but you believe the moat is durable for fifteen, you can make a case that shares are undervalued.

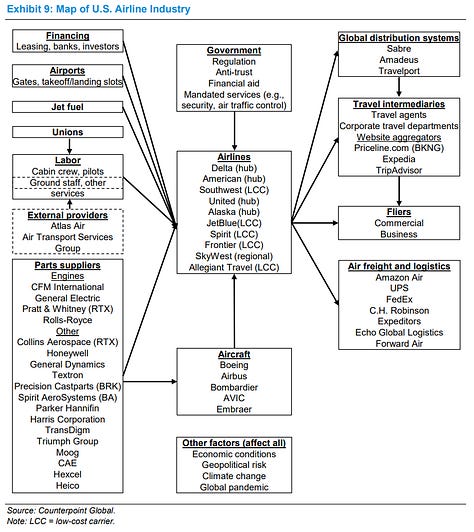

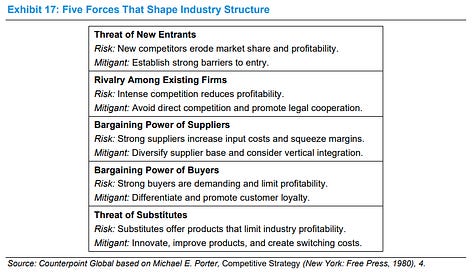

Analyzing the moat starts with the industry: mapping competitors, suppliers, customers, new entrants, and substitutes, and understanding where profits accumulate. You then evaluate stability, look at market share dynamics, and consider Porter’s Five Forces and disruption risk.

From Mauboussin’s Measuring the Moat article, I’ve attached a few images for you to get a better sense of industry analysis.

After the industry analysis, you analyze the firm itself: does it rely on differentiation or cost leadership, and what specific moat sources does it possess? Economies of scale, network effects, switching costs, and so on.

Ultimately, you’re trying to understand whether the company can resist reversion to the mean longer than the market expects.

Making Decisions

Decision-making is one of the hardest parts of investing. When to buy, what to buy, how much to size, and when to sell.

It’s also a difficult aspect of valuation. Mauboussin leans on Daniel Kahneman’s work here. He distinguishes between two views:

The inside view: focusing on the specific details of the firm

The outside view: looking at what happened to similar companies historically

Consider a $10 billion revenue company projecting 20% annual growth for five years. With the inside view, you look at the product pipeline, TAM, management team, and so on. With the outside view, you look at how many companies of that size have actually grown 20% for five years.

The outside view disciplines the inside view and forces you to anchor expectations in what is statistically likely, not just what sounds reasonable.

The Expectations Investing framework helps you value stocks without needing to do the heavy work yourself—that is, predicting the future. It gives structure to your decisions by grounding them in base rates and market-implied assumptions. It also helps determine which stocks to buy and when to buy them.

When market expectations embedded in the stock price differ significantly from both your perspective and the base rates, you buy (or sell). But valuation shouldn’t be considered in isolation; the moat and its longevity always matter. The market-implied CAP is useful here: if it’s short and you believe the moat will last much longer, you have a strong argument to buy.

When comparing buying decisions—and comparing stocks against each other—focus on the expectation gaps. For instance:

Stock A: priced for 2% growth; base rates, industry growth, and management targets suggest 8% growth is likely. The gap is large, making this a buy.

Stock B: priced for 20% growth; base rates suggest 25% growth is possible but rare. This is not a buy.

In short, the basic valuation framework rests on understanding:

What the market thinks (implied growth and CAP)

What analysts and management think

Whether this has happened before (base rates)

The moat and its durability

It’s simple and powerful.

At its core, investing is a game of expectations. Your job is to figure out where those beliefs are off and by how much. When the gap is wide, you act. When it isn’t, you wait. Most of the work is simply staying disciplined enough to stick to that process.

Thanks for reading.

Lucas,

Author & Founder, Summit Stocks

In case you missed it:

Disclaimer: the information provided is for informational purposes only and should not be considered as financial advice. I am not a financial advisor, and nothing on this platform should be construed as personalized financial advice. All investment decisions should be made based on your own research.

I really enjoyed the article.

Since we’re on the topic of horses and betting, this quote from Charlie Munger feels especially relevant right now:

"To us, investing is the equivalent of going out and betting against the pari-mutuel system. We look for a horse with one chance in two of winning, and that pays three to one. In other words, we're looking for a mispriced gamble. That's what investing is, and you have to know enough to know whether the gamble is mispriced."