LVMH: Empire of Luxury

A deep dive into the world's leading luxury conglomerate and its timeless desire

Hi, fellow investors!

Welcome back to another deep dive on a wonderful company. This time, we’re analyzing LVMH, the biggest luxury goods company in the world.

LVMH, also known as Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton, formed in 1987 when Louis Vuitton and Moët-Hennessy merged. However, the company’s roots go way back to the 18th and 19th centuries, with the founding of Louis Vuitton, Moët & Chandon, and Hennessy. Today, LVMH is one of the largest companies in Europe, generating more than €86 billion in revenue and €15 billion in profit in 2023. The business comprises six segments and 75 brands, which they call Maisons.

Table of Contents

1. History and Heritage

1.1 Louis Vuitton

1.2 Moët-Hennessy

1.3 Bernard Arnault—the Wolf in Cashmere

1.4 Arnault’s Vision at Scale

2. Contemporary Business

2.1 LVMH’s Business Model and Segments

2.2 The Essential Numbers

2.3 A Luxury Conglomerate’s Moat

2.4 Leap into the Future

3. Management

3.1 A Happy Arnault Family

3.2 Ownership and Compensation

3.2 Capital Allocation

4. Conclusion

1. History and Heritage

1.1 Louis Vuitton

Branding and heritage are crucial components of selling luxury goods. It is the combination of exclusivity, craftsmanship, quality, and heritage, that cultivates a sense of prestige, status, and desirability.

Louis Vuitton traces its heritage back to the 19th century, specifically 1854, when Louis Vuitton himself began crafting travel trunks in Paris. This era coincided with the rise of locomotives and ships as more popular modes of transportation. Vuitton was innovative in his craft, being the first to make flat trunks instead of the typical rounded ones. Rounded trunks were favored because their shape allowed them to shed water more effectively. Despite their flat tops, Vuitton successfully waterproofed his trunks, enabling them to be stacked on top of each other, a great convenience when traveling at the time. His innovative nature and craftsmanship quickly established him as a trunk-maker for the elite, and Louis Vuitton soon became a symbol of exclusivity and prestige.

Over the years, different types of trunks were developed with new innovations, including a revolutionary patented lock system and trunks featuring the iconic Monogram canvas (as seen in the above exhibit). The company expanded beyond trunks to include products like wallets and purses. However, Louis Vuitton remained relatively small until 1977, when Henry Racamier, husband of Louis Vuitton’s great-granddaughter, took over. He built the business into a global company. Under Racamier's leadership, Louis Vuitton went public in 1984 and subsequently merged with Moët-Hennessy in 1987.

1.2 Moët-Hennessy

Both Moët & Chandon and Hennessy trace their heritage back to the 18th century.

Moët celebrated its 280th anniversary last year, the company having been founded in 1743 by Claude Moët. This champagne producer soon became an international symbol of celebration and luxury. In 1833, the company was renamed Moët & Chandon as Pierre Gabriel Chandon joined the company as a partner of Jean-Rémy Moët, grandson of Claude.

Hennessy is a French producer of cognac, founded in 1765 by Irishman Richard Hennessy. He retired to the French Cognac region, where he began distilling and exporting brandies. Hennessy became the world’s leading exporter of brandy in the 1840s, and it is still one of the most well-known brands in the world.

Moët & Chandon and Hennessy merged in 1971. The businesses were complementary to each other, and both parties agreed it would be wise to join hands.

When Moët-Hennessy merged with Louis Vuitton, Moët-Hennessy was still the largest business revenue-wise. Nowadays, Louis Vuitton is the star of conglomerate LVMH.

1.3 Bernard Arnault—the Wolf in Cashmere

At the time of the merger, Henry Racamier led Louis Vuitton and Alain Chevalier led Moët-Hennessy. The current CEO, Bernard Arnault, however, led LVMH basically from the beginning. Interestingly, though, Arnault wasn’t involved in either company initially.

Arnault had been running the conglomerate Boussac, which specialized in textiles and strangely also owned the Christian Dior fashion house—the primary reason Arnault took over the conglomerate in 1984, when it was up for sale after going bankrupt, thanks to mismanagement. It was still a loss-making business when Arnault took over, and he decided to divest all businesses except Dior and the Le Bon Marché store. This was an unheard of decision at the time in France, as Arnault had to sack a substantial amount of employees—9,000 in just two years. He received the nickname ‘The Terminator’ from the press. It worked, however, and Arnault successfully steered the company back to profitability.

The primary reason for the merger between Moët-Hennessy and Louis Vuitton was to prevent external takeovers. There were no initial plans to synergize and integrate Moët-Hennessy and Louis Vuitton. The strategy was for both companies to collectively own at least 51% of the merged entity, ensuring protection from hostile takeovers. Racamier and Chevalier, however, didn’t trust each other and regularly clashed, and, as a result, both went in search for investors they could trust. Chevalier secured Guinness as a partner, while Racamier found support from a young Bernard Arnault, owner of Dior. Arnault, however, was (and still is) an ambitious man and he saw this invitation as an opportunity to take over the business.

What began as a measure to avoid a hostile takeover ended up resulting in one.

Arnault was successful in the end—he became LVMH CEO in 1989, two years after the merger, and Racamier and Chevalier were forced out of LVMH. He was nicknamed ‘the Wolf in Cashmere’ after the hostile takeover.

If you want to know the exact details of how the takeover happened, I’d highly recommend you listen to or read Acquired’s episode on LVMH.

1.4 Arnault’s Vision at Scale

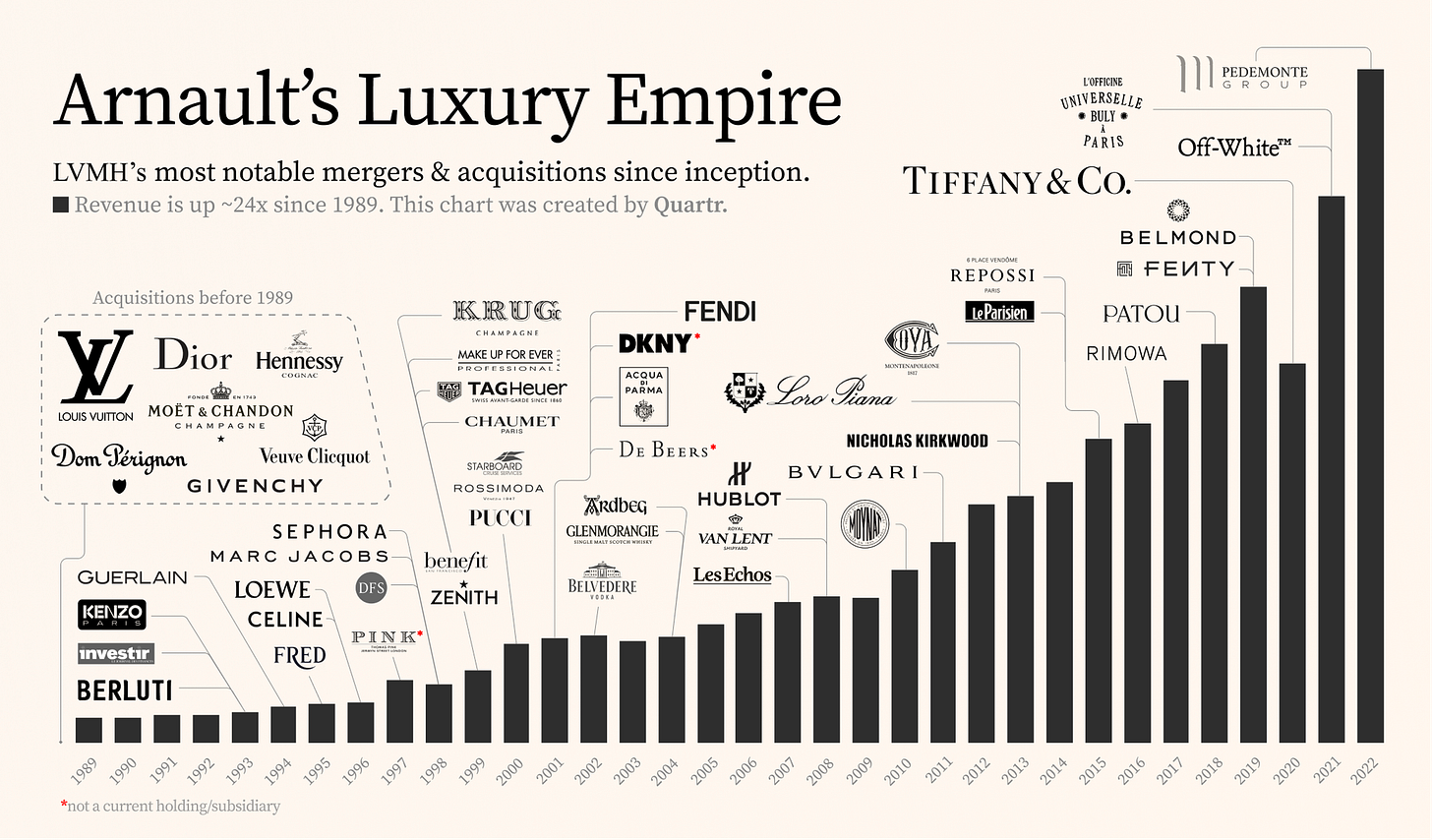

The year is 1989, Bernard Arnault is CEO of luxury goods conglomerate LVMH, comprised of Moët-Hennessy, Louis Vuitton, Christian Dior, and Givenchy (acquired in 1988).

Today, the company owns 75 brands, meaning Arnault hasn’t been idle between 1989 and now.

He’s always had a vision and ambition of owning and building up a luxury goods conglomerate, where economies of scale would take effect—an empire, so to speak. This already tells us a lot of valuable information about the contemporary company’s growth strategy, which is obviously focused on M&A. Through the company’s economies of scale, an acquired subsidiary almost always grows organically by gaining access to LVMH’s distribution networks, marketing budget, consulting, and other resources. However, an important part of the conglomerate is decentralization—LVMH’s subsidiaries keep the freedom they need to create and innovate while benefiting from the conglomerate’s resources. It is an impressive business model.

2. Contemporary Business

2.1 LVMH’s Business Model and Segments

LVMH operates in a decentralized manner, providing the resources each Maison needs to grow. This way, each Maison is creative, autonomous, and quick to react. And realistically, a conglomerate at this scale can’t possibly be centralized. Besides decentralization, vertical integration is an important aspect of the company, especially in protecting the brand equities. LVMH typically controls the entire value chain, from owning or closely collaborating with suppliers of raw materials, such as vineyards, to manufacturing and retailing. This allows for better brand control and cost savings.

LVMH is comprised of six business segments:

Wines & Spirits includes prestigious Maisons such as Moët & Chandon, Hennessy, Dom Pérignon, and Krug, among others. The segment boasts a total of 27 Maisons. LVMH produces wines and spirits through their vineyards, wineries, and distilleries around the world. The Wines & Spirits segment is the oldest within LVMH, also making it the most resilient. Although relatively small, it is an important segment as it helps shape LVMH’s heritage and authenticity. In 2023, the segment generated €6.6 billion in revenue and €2.1 billion in operating profit (32% operating margin), accounting for 8% of total revenue or 9% of total operating profit.

Fashion & Leather Goods includes high-end brands such as Louis Vuitton, Givenchy, Dior, Fendi, and Loewe, among others. The segment counts 14 Maisons. Although fewer Maisons than the Wines & Spirits business, it is by far the most important. The segment offers clothing, accessories, footwear, bags, and more. Flagship Maison Louis Vuitton has expanded from just trunks to handbags (and many other types of bags), wallets, shoes, ready-to-wear clothing, and much more. In 2023, the segment generated €42 billion in revenue and €17 billion in operating profit (40% operating margin), accounting for 49% of total revenue or 74% of total operating profit. Again, this is by far LVMH’s most crucial segment.

Perfumes & Cosmetics includes 16 Maisons, such as Givenchy Parfums, Fenty Beauty by Rihanna, Guerlain, Parfums Christian Dior, and Officine Universelle Buly, among others. These Maisons manufacture and develop a wide range of fragrances, makeup and skincare products. Compared to peers like L’Oréal and Estée Lauder, LVMH’s Perfumes & Cosmetics segment is relatively small. In 2023, the segment generated €8.3 billion in revenue and €0.7 billion in operating profit (9% operating margin), accounting for 10% of total revenue or 3% of total operating profit. The margins are also relatively low, making this segment one of the weaker ones. Despite that, the segment is important in spreading brand awareness for brands like Dior, as these products are often more accessible. It is a crucial part of the luxury ecosystem.

Watches & Jewelry includes Maisons like Bulgari, Hublot, TAG Heuer, and Tiffany, among others. Similar to Perfumes & Cosmetics, this segment’s offerings are complementary to the other segments. The oldest Maison in this segment is Chaumet, founded in 1780. Like the other businesses, the Watches & Jewelry business is active worldwide. In 2023, the segment generated €11 billion in revenue and €2.2 billion in operating profit (20% operating margin), accounting for 13% of total revenue or 9% of total operating profit.

Selective Retailing includes five Maisons: Sephora, DFS (travel retail stores), Le Bon Marché Rive Gauche (a department store), La Grande Épicerie de Paris (a luxury food hall), and 24S (an e-commerce platform). Especially Sephora is significant to the entirety of the segment. The international beauty chain was acquired by LVMH and operates more than 3,000 stores, with a strong presence in North America. That’s also why the segment derived 46% of its revenue from the United States. In 2023, the segment generated €18 billion in revenue and €1.4 billion in operating profit (8% operating margin), accounting for 21% of total revenue or 6% of total operating profit. It is a low-margin segment, but that’s to be expected from retail.

Other activities includes six Maisons. The segment is relatively meaningless in terms of revenue and profit, so I’ll discuss it in short. The segment includes luxury hotels, newspapers such as Le Parisien, a radio station, a café, and a yacht construction firm, among others. In 2023, the segment generated €0.3 billion in revenue and -€0.4 billion in operating profit.

2.2 The Essential Numbers

In the end, it’s all about the numbers. High-quality investors seek companies with:

Revenue growth that is consistent and sustainable.

Cash-generative business models, with significant and steadily growing free cash flow. Most, if not all, of net income should convert to free cash flow, and the company should have high cash flow margins.

Return On Invested Capital (ROIC) that is high and consistent, ensuring the economic spread (ROIC - WACC) is consistently positive.

Strong balance sheets.

Revenue growth is essential for any company’s longevity and sustainability. Without it, competition will catch up, and shareholder returns will be minimal since margins can only expand so much.

LVMH 5-year compound annual revenue growth rate is 13%.

Revenue was down in 2020 due to Covid, but it quickly surged back again as countries opened up. In 2023, revenue growth slowed down to 9%, and 2024 is expected to be a slow year. This is the result of the overall luxury goods industry taking a breather, after realizing rapid growth in 2021 and 2022. Over the long-term, revenue growth should be stable and I expect LVMH will be able to grow revenue consistently with high single-digits.

Cash flow generation is crucial to a business’ fundamentals. A company must generate high and consistent cash flow to become an attractive option for the high-quality investor.

As seen in the above exhibit, free cash flow has been declining since 2021. This is because of a combination of stagnant operating cash flow and increasing capital expenditures. Free cash flow being down because of increased investments is not a problem in my opinion. Net income is still growing steadily, and both net income and free cash flow should continue to grow in the future.

The same pattern can be seen in the company’s margins—operating and net margins have stayed relatively flat while free cash flow margins have dropped significantly. Again, I believe this to be a temporary setback due to increased investments.

Next, a company needs high and consistent ROIC before the high-quality investor even considers investing in it. ROIC is a crucial aspect of a company’s fundamentals. Generally, the cost of capital lies around 6-12%, so I only seek companies whose ROIC is above 15%, as ROIC must be above the cost of capital to create value.

For this deep dive, I decided to calculate ROIC myself. Every stock analysis tool tends to calculate ROIC differently, and I want to ensure the metric is valid and clear. That being said, LVMH’s ROIC is high enough, but it’s not spectacular.

ROIC has been slightly over 15% for the past 3 years, which is decent. One quickly concludes that LVMH is a business with a lot of intangibles relative to its tangible assets. In 2023, goodwill and intangible assets (brands, software, licenses, etc.) were valued at almost €50 billion on the balance sheet, while the company’s total assets were €144 billion. I also decided to include ROIC excluding goodwill to find out how much of an impact LVMH’s M&A strategy has on ROIC. As seen in the exhibit above, it’s a significant difference, with ROIC excluding goodwill being above 20% in 2023. To further exemplify the importance of LVMH’s brands and M&A strategy, I also calculated ROIC excluding goodwill and intangibles. It’s been around 30% for the past 3 years.

Now, you can’t just ignore certain assets—especially assets that are crucial to the operations such as brands—but by analyzing ROIC excluding goodwill and intangibles, we can find out that LVMH operates efficiently and lean.

A healthy balance sheet ensures the investor sleeps well at night. Risk of default is unacceptable for the high-quality investor.

LVMH’s total debt at the end of 2023 was slightly over €38 billion. Net debt (total debt minus cash and equivalents) was almost €31 billion. Free cash flow is around €11 billion, equating a net debt to free cash flow ratio of 2.81. This means LVMH is able to pay down all debt using their cash and equivalents and free cash flow (if free cash flow stays constant) within 3 years. Besides this ratio, I also analyze the balance sheet using the interest cover ratio. This ratio helps determine whether interest expenses are burdensome. It is calculated by dividing operating income by interest expenses. For LVMH, the ratio is 24, meaning the company’s operating income is 24 times higher than interest expenses. I like this ratio to be above 12, so LVMH passes.

LVMH has a solid balance sheet which indicates no risk whatsoever of bankruptcy.

2.3 A Luxury Conglomerate’s Moat

The moat, or sustainable competitive advantage, is crucial in determining whether a company will be able to continue to generate above average returns on capital. Without enduring competitive advantages, reversion to the mean is inevitable.

Firstly, LVMH benefits significantly from its intangible assets—obviously its brands. The conglomerate owns many of the strongest brands in the luxury goods market, fostering customer loyalty and enabling premium pricing. These brands signal exclusivity and luxury, thanks to their premium quality, rich heritage, high price points, and limited availability. Besides customer loyalty and pricing power, LVMH’s brands create high barriers to entry, as they are difficult to replicate. For instance, Louis Vuitton wouldn’t be such a prestigious brand if the man himself hadn’t been a master trunk maker for royalty in the first place. Heritage is an asset that cannot be replicated, certainly not in the short-term. LVMH’s brand power is reflected in its gross margins, which near 70%.

The LVMH brand is also strong at the corporate level. Thanks to its reputation, LVMH attracts top talent. Moreover, individual brands that seek to be acquired typically prefer to sell their business to the best buyer, which is LVMH.

Secondly, LVMH enjoys economies of scale, a competitive advantage Bernard Arnault has been pursuing since he purchased the conglomerate Boussac, which included Dior. Contrary to popular belief at the time, Arnault believed that luxury brands could be larger than anyone at the time imagined. Traditionally, scaling and reaping the benefits of scale in this industry were considered impossible because scaling an exclusive and prestigious brand typically deteriorates the brand itself. For instance, when an exclusive handbag is available on the shelves of every retailer, it loses its exclusivity. Similarly, when a luxury car is seen frequently on the roads, it loses the perception of being rare. This highlights how brands can be vulnerable to mismanagement and the importance of maintaining their exclusive appeal.

In essence, luxury good companies need to be careful with their growth strategy, because growing a single luxury brand too quickly can deteriorate the brand. Arnault, however, realized that economies of scale could still be possible in this industry if you own multiple brands.

“[It was] an idea I had after having bought Dior. I saw how the luxury market was made up of many medium-sized companies that, taken together, could be much stronger in a group composed of several brands.” — Bernard Arnault, in an interview with Bloomberg.

A luxury goods group is economically much stronger than a single luxury goods brand. Thanks to LVMH’s extensive portfolio of brands and subsidiaries, the company enjoys significant economies of scale while ensuring that each brand is carefully managed to maintain its value. The conglomerate’s scale allows for:

Shared resources across its Maisons, such as distribution networks, suppliers, and production facilities, which greatly reduce costs.

Access to significant capital to:

Acquire other companies;

Invest in property, plant, and equipment, such as buying the best retail locations;

Spend on innovation through research and development;

Run extensive marketing campaigns, often featuring celebrities (the most recent example being LVMH sponsoring the Paris 2024 Olympics with an investment of €150 million).

LVMH’s scale allows for better operational efficiencies and provides much more firepower compared to its competitors.

LVMH’s strong brand portfolio and economies of scale have allowed the conglomerate to compound at above average returns on capital. I consider the company to have a wide and sustainable moat.

2.4 Leap Into the Future

A company needs to operate in growing industries if it aims to keep growing. A growing market is one of the most important growth drivers for companies.

Fortunately, LVMH finds itself in a favorable position, benefiting from multiple secular trends.

Almost 40% of LVMH’s sales are derived from Asia, including China, Japan, and India. These countries are experiencing higher GDP growth rates than the Western world, driving increased consumer spending and a rising middle and upper class. Especially countries like India, with a population of more than 1.4 billion people, are still in a nascent stage compared to Western countries. With 40% of sales in Asia, LVMH is well-positioned to capitalize on these growing economies. Other emerging markets, such as Latin America and the Middle East, should also become growth drivers for the conglomerate.

Additionally, there is a long-term trend of increasing global wealth. The wealthier the world becomes, the more people will have access to luxury goods. Since humans often desire to reassure themselves of their status by purchasing expensive items, LVMH is poised to benefit.

These two long-term trends are the most significant for LVMH—they have the biggest impact on the company.

3. Management

3.1 A Happy Arnault Family

LVMH has been run by the same CEO since Bernard Arnault took control over the company. He’s been running the company for more than 30 years. Arnault is now 75 years old, but he doesn’t show any signs of retiring soon. In fact, he recently raised the CEO retirement age at LVMH from 75 to 80. It’s great to see how he’s still passionate and driven to continue with his role, but a succession of leadership is inevitable, albeit not in the short-term.

Chances are high that Bernard’s successor will be another member of the Arnault family, whom Bernard has been grooming by having them hold key positions within the company.

It’s important to realize that none of Bernard’s children were given their roles just because of their close ties to him. They’ve had to work for and deserve their positions.

Delphine Arnault, born in 1975, is Bernard’s oldest child. She is CEO of Maison Dior, one of the most important brands at LVMH, holding a prominent and responsible role within the company. Delphine attended EDHEC Business School in Lille and the London School of Economics. She began her career as consultant for McKinsey for two years before starting at Dior in the shoe department, where she worked from 2001 to 2013. There, she rose to deputy managing director. Following her role at Dior, she became executive vice president at Louis Vuitton until 2023, when she became CEO of Dior.

Antoine Arnault, the second child, was born in 1977. He began his own business in 2002 but sold it when he joined LVMH’s marketing team. Meanwhile, he earned his MBA from INSEAD and worked his way up to become director of communications at Louis Vuitton. In 2018, he became CEO of Maison Berluti, but he recently left this role to become CEO of the holding company Christian Dior. There is a crucial difference between Maison Christian Dior and the holding company: the holding company is Bernard’s first company, previously Boussac. With it, he acquired a large stake in LVMH at the time of the takeover in the 80s. Nowadays, the holding company owns a significant portion of LVMH, large enough to have majority control. Antoine becoming CEO of the holding company may signal future succession plans. Both Antoine and Delphine sit on the board of LVMH.

Alexandre Arnault, born in 1992, is Bernard’s third child. Bernard’s three youngest are half-siblings of Delphine and Antoine, as Bernard married Hélène Mercier, with whom he had three more children. Alexandre graduated from Télécom ParisTech and earned a master’s in innovation from École Polytechnique. He became executive vice president of product and communications at Tiffany & Co when LVMH acquired the company. Before that, he was CEO at Maison Rimowa. Alexandre has already had a significant influence on the Tiffany brand, launching major marketing campaigns with couple Jay-Z and Beyonce, and other celebrities like Gal Gadot, Zoë Kravitz, Elaine Zhong, and Jimin, among others. Such campaigns are examples of LVMH’s economies of scale. Tiffany, as an individual entity, would never have been able to finance such expensive marketing campaigns, but as part of LVMH, they had enough capital.

Frédéric Arnault, born in 1995, was named CEO of TAG Heuer at 25 years of age. He studied at École Polytechnique and also ran a startup before joining LVMH. Since 2024, he has been appointed CEO of LVMH Watches, overseeing all the watch brands.

Jean Arnault, Bernard’s youngest child, was born in 1998. He earned two master’s degrees, one in mechanical engineering and the other in financial mathematics. Like Frédéric, Jean is especially interested in watches, which is why he became director of marketing and development for Louis Vuitton watches.

The question remains who will succeed Bernard when the time comes, but the most likely candidate seems to be his eldest son Antoine. One thing is certain: all five of Bernard’s children are very competent and involved with the company. I believe LVMH’s future is safe.

3.2 Ownership and Compensation

It is important for management to have interest aligned with those of shareholders. Management often has similar interests when they are shareholders, preferably large ones. Bernard Arnault is one of the wealthiest men in the world, thanks to his significant ownership in LVMH.

As of December 31, 2023, the Arnault family group held 48.6% of shares outstanding, with voting rights of 64.33%. Bernard Arnault wants to maintain majority control of the company, as he knows from experience what can happen when you don’t hold control: your company gets taken over through a hostile act. He’s experienced this first-hand.

This large ownership of shares means that management will make decisions to create maximum shareholder value over the long term. Compared to his compensation, Arnault naturally holds a substantial position. He was compensated about €3.3 million in 2023, while the Arnault family group stake is worth roughly €162 billion.

3.3 Capital Allocation

A crucial task of management is deciding where capital should be allocated. A significant portion of LVMH’s operating cash flow is allocated toward capital expenditures, and the conglomerate pays out a large portion of its free cash flow as dividends. The payout ratio has increased drastically over the past two years, as dividends kept increasing while free cash flow decreased due to increased capital expenditures. Of course, LVMH ensures there is enough capital available for potential acquisitions, which is an important part of their strategy. Normally, I’m not a huge fan of an M&A strategy, but LVMH is one of the best acquirers, where they apply some sort of magic formula to acquired subsidiaries to make them grow quicker than previously possible.

In short, LVMH’s capital allocation strategy consists of M&A, capital expenditures (mostly maintenance, but in recent years also for growth), and dividends.

4. Conclusion

The power of a strong brand is immense. It allows for higher margins, customer loyalty, and it creates barriers to entry. LVMH is a conglomerate with some of the world’s strongest brands. Beside this, Arnault has created significant economies of scale within his company. The Wolf in Cashmere, ruthless and iron-fisted, has an exceptional track record and his children seem strong candidates to take over his role when the time comes.

LVMH is a high-quality company with a rich history. It is a company that that fits all my needs as an investor. As a result, I’ve added LVMH to the Investing202 Portfolio. I’ll provide more on that in the upcoming portfolio update.

Thank you for reading this far. I hope you’ll have learned a ton about this company. If you want to read further and learn more, I’d suggest the following sources as a starting point:

Stay tuned for more deep dives on other wonderful companies!

Disclaimer: the information provided is for informational purposes only and should not be considered as financial advice. I am not a financial advisor, and nothing on this platform should be construed as personalized financial advice. All investment decisions should be made based on your own research.

It was estimated by HSBC in a FT article

What do you think of the group's reliance on Louis Vuitton and Dior which make up 71% of profits?